Trying to Rewrite History // by Sean Koa Seu

Book writer and lyricist Ellen Fitzhugh is assigned the near-impossible task of not only rewriting her musical, but righting the wrongs.

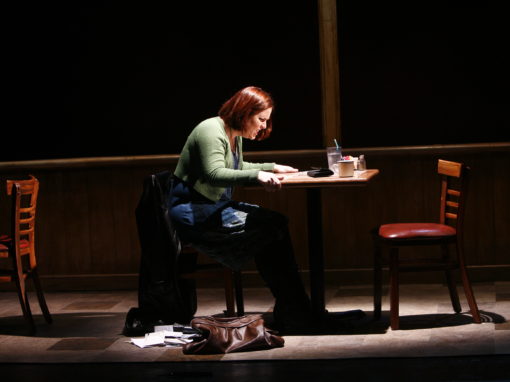

Ellen Fitzhugh, librettist, is a small but mighty white lady. A witty and rambunctious lyricist, blessed with an innate sense of rhyme and meter, she’s of an old-school stock not easily found today. I munch on almonds and watch her work at her desk—as Assistant Director, it’s my job to turn her notes from chicken-scratch to type—and occasionally I answer her questions. I’m half Chinese, I say. She’s full white, she laments. She asks me if the cigarettes bother me. They don’t, I tell her.

She takes her notes by hand, with penmanship only a writer can read, holed up in one of the last smoking rooms in Manhattan. And she is smoking a lot, and guzzling a lot of coffee, because, well, she’s been assigned a rather gargantuan task—she is trying to rewrite her story.

A miserable ordeal for any writer, but for Ellen, a particularly difficult one. In her case, this is a feat that normally takes generations of historians to get right. Because this revision isn’t any old revision. For it must incorporate something new into the story, something which has, until now, gone unacknowledged—race.

Her short musical, Just One Q, was originally commissioned in 2016 by New York’s Premieres for its biannual “Inner Voices” program, a compilation of one-act solo musicals. The show featured a squabble over a scrabble game, between two elderly white women fighting over the memory of their former lover. In the first draft of the script, there was not a single Black character—indeed, this script was based on Ellen’s own family history. But the work began to transform when Benny, the nursing-home orderly who relays these women’s stories to the audience and whose race was originally unspecified, became Black.

Funny, isn’t it, what a difference casting can make?

And so, in the original production of Just One Q, it is Benny’s Blackness itself—uncommented on, but ever present—which brought to the show a racial component that was mostly supplemented by the audience’s own experience.

The story of Just One Q survives in Broadbend, Arkansas but it is now written into a context much beyond the scope of the original work. Harrison David Rivers, librettist for the second act, forces the audience to confront the racial aspect of Ellen’s original story. And he doesn’t have to invent all that much—rather, he follows Benny’s life to it’s inevitable conclusion, and passes the torch to Benny’s daughter, a Black woman in the South, now beyond the insulated walls of the nursing home and set adrift in a world of police brutality and Black death.

This is the story of our republic. It is the story of America, circa 2020. The story of our nation—the stories of Columbus, of Thomas Jefferson and the Declaration of Independence, of the Confederacy, of the Great Emancipator and of JFK and LBJ, are all suffering from an appalling lack of Blackness. It is now, with the murder of George Floyd at the hands of the police, exacerbated by a virus that disproportionately kills Black people, that we are finally learning what an enormous task it is to rewrite our history—to let go of the stories which have perpetuated so much suffering, and to acknowledge the Truth.

It is not a task for one woman alone. Nor did she do it alone—Harrison’s heart-breaking text provided many opportunities for Ellen to reacquaint herself with her character. And that’s what it was—she was meeting Benny, a character she had written into existence, on his own terms. He could no longer just be a nursing home orderly. He had to go beyond the nursing home to “tell his own story.”

It’s fascinating, the way art can start to have a mind of its own—the way it can begin to communicate a Truth beyond one’s own experience.

And so, Ellen turned to history for help. She researched the Freedom Riders, sit-ins, protests, the Civil Rights Movement, Parchman Farm. And she came back with a draft of her work that now featured Benny—not just an orderly, but a father, with an adventure of his own.

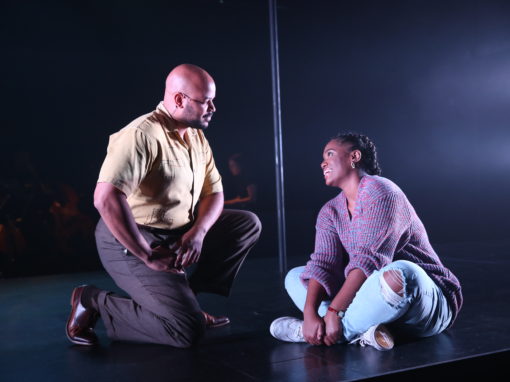

Of course, the revisions didn’t stop there. History, as we are learning, can only teach us so much. And it is always, in this country, molded by whiteness. And so, the revisions kept coming—Justin Cunningham, who plays Benny, acted as steward to the work, trying to marry his lived Black experience to Ellen’s historical context.

The process was, in all fairness, fraught. I believe anyone on the team could tell you that. Musicals, as they come together, are always mini-nightmares—it is the task of the theatre-maker to transform that nightmare into an audience’s dream. But what continued to impress me about the collaborators of Broadbend, Arkansas was their dedication to the work—the sense that these rewrites were important, not only to the artistry of the piece, but to the integrity of the story. That these rewrites were making a difference—not just so that the audience could understand the story, but so that the audience could understand its own country.

And so, Ellen took on the task of rewriting her own story—of recontextualizing it in Truth. She took on the task of a nation—a task that every white person in this country must take on today. Not an act of charity either, but rather, an act of duty, an act imperative. The process wasn’t easy. I watched her write the same lines over and over, her pen shaky. I watched her, hand in forehead, staring down at pages and pages of text. Maybe what she attempted is impossible—many people believe that. To rewrite our history is one of the hardest endeavors we can take as a country. It will take many lifetimes. And it will never be perfect.

Ellen didn’t let that stop her. And neither can we.

About the author:

Explore Our Past Shows