The Pride and Pitfalls of Rosa Gonzales // by Elena Hurst

Actor Elena Hurst wrestles with the complexities that come with playing a Latina character written in a different era.

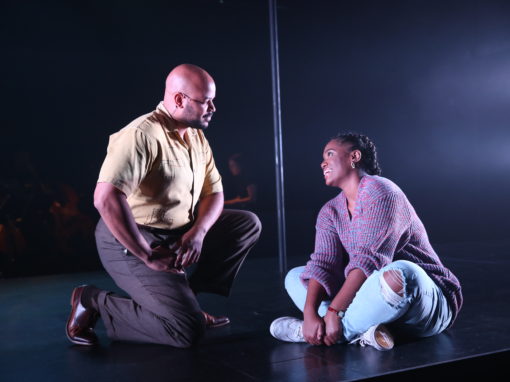

Tennessee Williams’ Summer and Smoke opened in May of 2018 at Classic Stage Company in Union Square. Opening night was a truly sweltering affair, well over 80 degrees, and I was over the moon (Lake Casino!) to be making my Off-Broadway debut in this monumental co-production with Transport Group Theater Company. I recall that whole time like a dream. I was working with a cast of powerhouse actors whose work I had admired and who I only grew to love more. I got to share a dressing room with dynamic, energetic women, and like my character, Rosa Gonzales, I was engaged to be married and full of optimism for the future. There was an easy and exciting rhythm to life for me during that production. I lived off the L train in Brooklyn, and it was a few quick stops to the theater. I would meet my friends at our favorite bar a couple blocks away after the show, and when they asked me how I felt, I would reply, “Happy. I get to go and make this beautiful piece of art every day.” And indeed, it felt like our show, our story, existed on a freshly stretched canvas. Our bare white stage and dropped white ceiling void of any props, save the picture of the fountain with the angel on an easel, so beautifully designed by Dane Laffrey, gave me the feeling of being suspended and taut in space and time. Like living in a master’s painting.

But playing Rosa Gonzales had its pitfalls and heartaches as well. The gross stereotype of a sexualized, “hot-blooded” Latina was something I had to work against with not many lines or scenes to do so. And performing her every night for a largely white audience felt like I was playing into a hand that Latina actresses had been dealt for far too long. I remember eagerly going to the talkbacks anticipating questions from audiences about how we approached this delicate matter. But no one ever asked. Had we created such nuanced three-dimensional characters with Rosa and Papa Gonzales that the audience didn’t see the need to ask about playing such potentially offensive characters? Or were people so used to seeing us this way, they simply didn’t see the harm?

Summer and Smoke, set in Mississippi in 1916, explores the conflict between the pleasures of the body and the aspirations of the soul. When dashing doctor John Buchanan returns home for the summer, he is magnetically drawn to the preacher’s daughter, Alma Winemiller, but their stars never seem to align. Rosa Gonzales and her father have also come to town and operate the Moon Lake Casino where John spends his nights reveling in all the earthly pleasures Alma finds so sinful. A love affair and engagement between John and Rosa ensues that ultimately ends in tragedy. In many ways, Rosa’s character is meant to personify lust and passion, and all the ways in which Alma can never fully act. But the trap is that these are the same hollow tropes that have been used to portray Latina women in popular American culture for centuries.

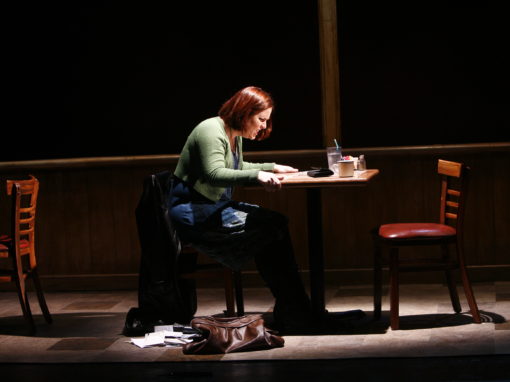

I remember one afternoon in between our matinee and evening performances, I was working on an audition for a role that didn’t feel all that different from Rosa, though written several decades later. I complained to a castmate that I was tired of “being a crayon in a box.” I didn’t want to play stereotypes like this anymore. He told me fine, but if there was ever a time to do it, it was for this revival of Summer and Smoke. We laughed, but the truth in his response, was that I did feel a deep sense of pride and responsibility to portray Rosa, and Latinx characters in general, with the intention and care and voice I knew I could give them. And furthermore, the Rosa and Gonzales Family we crafted for this show were deeply rooted in truth. We had lengthy conversations about the era, contextualizing their experience in the history of the Mexican-American War and the Mexican Revolution, and what being business owners in a Southern town at that time would have looked and felt like. We looked at Tennessee Williams’ own tumultuous relationship with Pancho Rodriguez on whom Rosa is thought to be based. And we explored the deep parallels between Rosa, Alma, and Johnny’s relationships with their fathers. All three felt stifled and trapped in similar ways. I hoped that these parallels made Rosa’s character feel more universal and complicated and less like a caricature both in my body and to the audience. And then there were the subtle choices and constant questions to be answered. I remember our director, Jack Cummings III, asking me if Rosa was tipsy at her engagement party, and I decided, no. My Rosa had to keep an eye on the casino and her father who definitely was drunk. She’s a woman who has to look after Papa, and the business, and leering men, and angry white neighbors, and so drinking is not something she has the luxury of doing. And then, a fellow Latina actress and confidant asked me if I thought Rosa had ever been with a white man before Johnny. I thought definitely not, and that opened her up to being someone not impulsive and lustful about Johnny, but fiercely protective of their relationship, and deeply hurt by Johnny’s attentions on Alma.

And yet, to this day, I have always had doubts about my choices. Was I letting Rosa speak to me on her own terms? Or was I so worried about not playing the stereotype that I missed opportunities to let her speak her truth? It is a question and a burden I’m sure many artists from marginalized communities have to confront in their work regularly, and especially now as our stories and narratives and collective traumas are being brought to the forefront in traditionally white spaces. When do we stop worrying about the white gaze and start worrying about unpacking our own truths? And when do we stop fighting to play the stereotype and start fighting to play everything else? Is there a world where I could play Alma and what would that mean for the actor playing Rosa? What would that mean for the audience? In the end, these questions aren’t answered on the page but at the theater with artists and audiences willing to explore the depths and universality of these human experiences. I know that each night of that sweltering summer of 2018, as I took my place at the top of the show, waiting in the wings for my entrance, I felt a profound sense of resolve, of pride, of joy, of sorrow, and of wonder for what was yet to come. I knew I was stepping on to a master’s canvas, and I had the unique opportunity and freedom to bring as many crayons as I wanted.

About the author:

Explore Our Past Shows