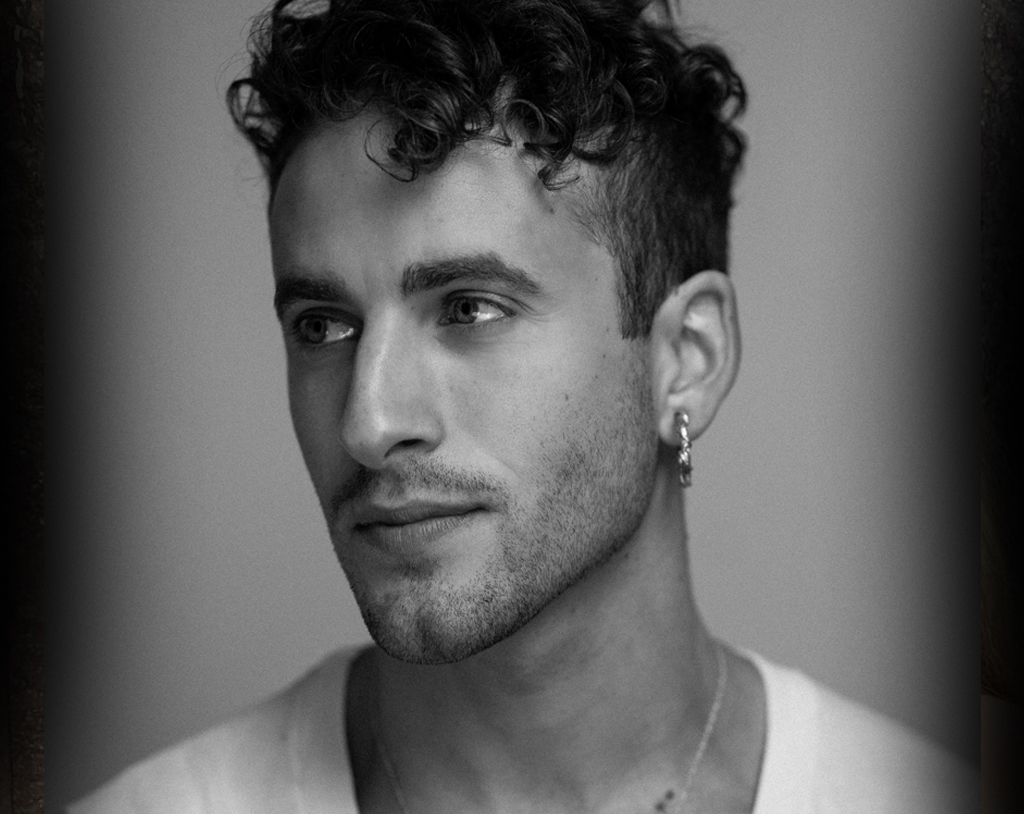

The Comfort in “Creature” // By Danny Kornfeld

Actor Danny Kornfeld cracks open his artistry by owning his uniqueness in RENASCENCE.

On the very first day of rehearsal for Renascence, Carmel Dean and Dick Scanlan’s world premiere musical about the life and work of American poet Edna St. Vincent Millay, six actors sat around a table in the basement of the Clinton Cameo Studios (a beautiful dungeon of a rehearsal space) where we would begin to dive into Millay’s world. I was terrified—I had only recently graduated from college and had just as recently “come out” and I still doubted myself constantly. But as Dick (who was also co-directing with Jack Cummings III) looked around the room, he assured each of us of our essential place in telling this story: “We have cast six distinct creatures here. And that is what will be most exciting to explore. Yes, this is a story about Millay, but this is also the story of YOU.”

Creature. The word struck me powerfully that day, and it stuck.

My first association with the word was the image of myself when I emerge from my bedroom every morning—my Jewish curls springing from the top of my head in a gigantic poof—very creature-like! Or consider the special knack I have for naming every dog I pass on the street based solely on my read of their spirit. “Hi Norma Joe!” “Hello Marble.” That seems creature-ish too… (or am I just plain odd??) Nevertheless, what Dick and Jack were emphasizing was the necessity in identifying and highlighting what made each of us unique individuals. I remember my surprise—they want me for ME? What a concept! As I said, I was green (I got my Equity card from this show), and I found myself intimidated by the impressive company I suddenly found myself in. I had spent most of middle school shuffle ball-changing around the kitchen to the original cast album of Thoroughly Modern Millie (another Dick Scanlan masterpiece). In college, my jazz teacher would make us do pirouettes to the tune of my fellow castmate Katie Thompson’s cover of “Heaven is a Place on Earth” (listen to it, trust me). In comparison, I was young, inexperienced, and didn’t yet grasp what made me special. All throughout my adolescence, I was conditioned to consider—“How can I fit in? How do I avoid being other? How do I give people what they want and need?” As an actor, I felt I needed permission to make nearly any choice. And here were Dick and Jack insisting that my own story was important.

It was through Vincent (Millay went by her middle name) herself that I began to understand the deeper meaning of my own “creaturehood.” She was precocious, brilliant, rebellious, confident, and uninhibited. She allowed herself a freedom that was at the core of her self-actualization. She was the epitome of “creature.” She was a complete libertine who defied expectations of both gender and sexuality—in the first decade of the 20th century no less. She leaned into every facet of herself in an environment of enormous conformity. Her magnificent poem “The Ballad of the Harp-Weaver” made her the youngest female poet to ever receive The Pulitzer Prize for Poetry. Her sense of singularity and confidence was—and still is—extraordinary.

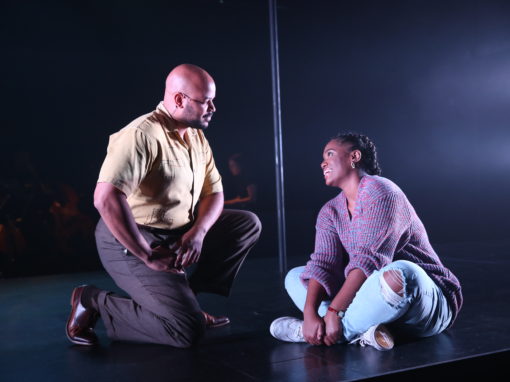

I began to understand that true artistry requires the embracing of that very same creature’ness that drove Vincent. I allowed myself questions I had never dared to ask before: What is the “other” in me? What is special about my energy?—my sense of play? Where does my talent actually lie? Ultimately, I knew the answers were deep in my bones, but how could I trust them? Thankfully, in the beginning, Dick and Jack trusted what I couldn’t yet. The two roles I played were both across gender—Vincent’s sister, Kathleen, and an older benefactress named Caroline B. Dow (the choice for my casting was to highlight Vincent’s own fluidity) and the last thing I wanted was to play an “idea” of these women, or to be a caricature. After weeks of struggle and doubt, and with patient reminders from both Dick and Jack, I slowly began to trust the creature they saw in me while also allowing myself to sit in the unknown without the need to have it all figured out. I was granted the opportunity to sit in the discomfort—to fail, to question, to explore, and to trust even before there was clarity. Ultimately, it was through trusting my own humanity that I found success in portraying the humanity of these women. Even more beautiful, the more the six of us continued to embrace what made each of us so uniquely different, the more cohesive the storytelling became. While you’d think it would have the opposite effect, this piece called for it. Millay exemplified it and Renascence needed it.

I now realize that my favorite kind of artist is my favorite kind of human—someone who proudly and unapologetically owns every facet of themselves. This is self-love in action. And while I know it’s a life journey and an impossible goal to permanently achieve, I am so grateful that Transport Group set me on that journey—one that I will continue to foster, illuminate, and love myself for. This is what makes Transport Group so special, and it’s evident in everything they do. There’s nothing convenient or conventional about the stories they tell and the ways in which they tell them—there’s absolutely nothing generic. Each story is an event in which the line between story and spectator vanishes. And as we begin to re-enter rehearsal rooms and fill theaters, I hope we are all asking ourselves, “Do we really want to return to a theatrical world that feels cookie cutter and complacent?” Or do we follow in the spirit of Transport Group? How can we celebrate the other? How can we enrich and enlighten our art and our world through a commitment to uniqueness? We are in a moment in time when we have been forced into stillness, to sit in silence, to question within the uncertainty. I am hopeful that this time to reflect will really result in meaningful change. The only way I can envision lasting change is to find the creature in ourselves and to use that power to celebrate the very same in those around us.

At the end of the poem Renascence (which was also the final moment of our production), the narrator has been swallowed up into the earth, faces death, and is consumed with terror as she sees the interconnectedness of the world. Only after this, she is spit back out onto the earth again, and says:

The world stands out on either side

No wider than the heart is wide;

Above the world is stretched the sky,—

No higher than the soul is high.

The heart can push the sea and land

Farther away on either hand;

The soul can split the sky in two,

And let the face of God shine through.

Like Millay’s narrator, I am reminded to widen my heart and stretch my soul every day, and I invite you to do the same. The more we continue to embrace, feed, and foster the creature in us all, the more fruitful our art, our relationships, and our world.

About the author:

Danny Kornfeld made his Transport Group debut as Aunt Caroline in the critically-acclaimed production of Renascence. Other Off-Broadway credits include Wringer at City Center; directed by Stephen Brackett. Previously he toured as Mark Cohen in the 20th Anniversary Tour of RENT. He has done both plays and musicals regionally at Barrington Stage Company, Syracuse Stage, and Theatre Aspen, as well as developmental workshops and labs at The Eugene O’Neill Theatre Center, NAMT, and The York Theatre. Check out the debut music video he directed, filmed, and edited for fellow Renascence castmate Hannah Corneau’s latest single “Miracle Mile” https://youtu.be/qJqcVMJgzDk

Explore Our Past Shows