Notes From the Field of Acting // by Nathan Darrow

Actor Nathan Darrow gives us personal insight into his experience of playing John Buchanan in SUMMER & SMOKE.

“The magical places that are within all of us broken, desperate people.”

– Tennessee Williams

1. How I Got The Job

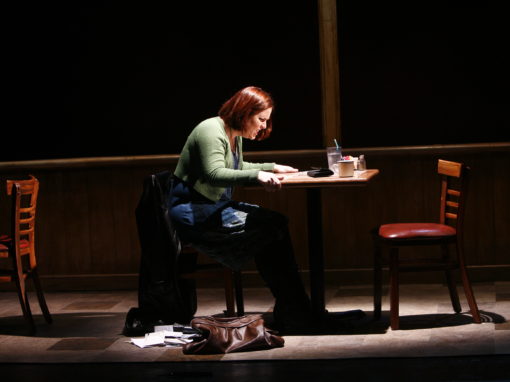

I had no job. But that’s normal for an actor, they get used to it … Said no one. Ever. Regarding moi. I do fantasize about learning languages and trades, taking trips and connecting with people, or just contentedly managing the normal responsibilities of a family member and householder, free of the mental and physical demands of working on a part. It has mostly never gone that way. Usually I finish something, I am briefly happy, and I wait to suffer. And then I begin to suffer for real. I had been working a good bit in the stretch leading up. Only a few months prior, I had played Hamlet in my hometown. I am sure now that most actors who play that part even to a modest level of success are likely to begin to think they may be capable of doing something on the stage that’s worth a darn. I was no different on that day early in the fall of 2017. It may not be correct thinking on the actor’s part but confidence, while certainly not everything, can be a big help. So, with no project and none coming up I brought myself to a nearly empty, sun-drenched room. I closed the door and sat there with the text of some old serious play in my lap and made as if I had some work to get on to. It’s kind of embarrassing but I just don’t know what else to do. Actors are artists with no violin to pick up. No pen to take out. We cannot practice purely like that — like get to do more or less the actual thing whenever we wish. So how in heck are we meant to work when we are not, at the moment, wildly fortunate to be working on something? How do we practice? Stay sharp? Develop? Well, we figure it out, I guess. And that’s what I came up with that day. Big old serious play. Pretend you are cast and get to work. So, I began.

Three and four-tenths of a second later my attention flagged. I called a break and accessed the world wide web to find out what could possibly be so occupying the world of my profession that it would ignore me on this sunny day. Now this is another thing actors do, and I am embarrassed that I do it and sure feel sheepish to now be writing about it, but we sniff around media to find out what is going on. What productions are happening? Who got that job I was up for (for a minute) and was sure would change my life forever? I guess it’s normal. Not totally embarrassing. But I’ve got a big serious play in front of me, and I can use the next five minutes to feed my imagination and my soul. Yes, yes you can. That doesn’t mean you always will. And that is all part of the whole thing too …

First news I see is an announcement for a production of Summer and Smoke that Transport Group will produce with Classic Stage Company and Marin Ireland will play Alma. Well now I am a little glad I called that break. It’s a play I know. It’s one I have even worked on with a partner and a great acting teacher and—I think—started to get somewhere with. So, I let myself think for a little while about my suitability and what a cool thing it would be to get to do. I knew Marin’s work from one performance onstage and the energy and variety of life she shared were deeply imprinted in my organism. It was acting that was thrilling and significant and—I would say—of great value to the wider practice of making work in the professional theater. A raw nerve shot through authentic talent, intelligence, and art. This is an actor, for sure, and this is an actor who should play Alma Winemiller. Then the mind journeys on when one is alone in a mostly empty room as the light starts to make everything magic. This is kind of a fancy deal and they’ve got someone strongly in mind probably. Yes, for sure they do. For sure they would. John Buchanan, Jr. will be played by some well(er)-known, strapping(er) actor or movie star or tee-vee star or Insta-star. It will be beautiful and a triumph. And that is all okay. I am and have been so, so fortunate. Sigh. Back to Woyzeck.

Not twenty-four hours later fate spoke up in an e-mail from agents that I had an audition for this durned thing. Ok ok. So much for journeys of the mind on sunny afternoons. A good lesson for the future which I will one hundred percent incorporate for the rest of my life in all things … like you do.

I began preparing immediately.

It’s nice when your thinking is positive about something you are up for. They should absolutely hire me for this. They may not of course. Let’s face it, they don’t usually. But regardless, this time they absolutely should. It’s a weird thought/feeling also. Is it arrogant? Is it confrontational or narrow or anti-creative? Maybe but sometimes it is just right there, and it doesn’t hinder a person’s work. It probably helps it. This was my situation through the process of getting the job. When I learned I was hired a heavy dopamine flush ran into multiple synapses and a flood of highly pleasant sensations filled my body. I was really, really happy to go up into that mostly empty room that gets soaked in magic light toward evening. To go to work.

2. The Play / Working

Many very enjoyable plays and performances are thin on poetry. It’s not essential for a piece’s success in the theater. But the produce of a real poet-playwright is shocking and wonderful. People are brave to sit in the dark with strangers not long before bedtime and open themselves to poetry in particular. Hearing a story before bedtime makes sense. But poetry is not a story. I don’t know what it is. I can try to articulate its effect. I know in my case that effect is that I can be truly nourished and seriously troubled, simultaneously and all at once. And I know that when it “happens” it feels like contact is made with a reality and an existence that is very very large—so large it doesn’t seem possible that it is available to me. But it is. Or maybe it’s the feeling releasing the lies that are buried so deeply I don’t notice their cost. Yes, I think it is probably more that. It can cleanse. I have been washed by it. And sometimes when the lies and the muck have become particularly thick, the bath is startling and even painful.

Alma enters the stage with a desire to be cleansed. She is only ten years old, but she knows this need already. She comes to an actual fountain with reverence, alone, and drinks cool water. It’s the play’s prologue and John, also ten, enters looking for her. John’s mother has died horribly, and his father is overworked and grieving so John’s body and clothes are less than clean and fresh. Alma has put a new box of white handkerchiefs on his school desk. He is dirty; she understands why, and she wants to help. She wants him to be clean. He scorns her gift, and perhaps with too much emphasis to be believed, announces indifference to his hygiene, and her kindness. He goes to the fountain and takes a drink like he owns the thing. The fountain is a stone angel, and her name is a poem composed of one word. It is carved into the base. Alma knows the poem well. She instructs John.

…it’s all worn away so you can’t make it out with your eyes. … You have to read it with your fingers. … Go on! Read it with your fingers!

(With his fingers John reads)

Eternity.

And in an instant the two are together, washed in the sweet terror of poetry. It is terrific theater. Tennessee read scads as a child. He never stopped and became an extraordinary reader. He read widely and closely. I imagine him as a child, ill in bed, surrounded by books, responding physically and immediately like Alma and John to the words themselves. Repeating them and scaring himself and loving it. The reader loves it when they are taken by the sentences and carried at a clip. Sometimes though they are stopped—pinned through the throat to the back of the chair—by a word or a sentence and they can’t go on for a good few moments. This is Tennessee, and John, and Alma, and us gathering in the evening with a wish to be burned.

To have some time between getting a part and beginning to rehearse can be a big help to an actor. Not always. And sometimes little or no time is a great benefit. There will be the moments of performance and we all gotta be there right then, and what we found in rooms with nice lighting in the months before do not accomplish the essential acting stunt—to be present and to play at a given time and a given place. It’s harder than it should look. Actors work like demons for decades and lifetimes to pull it off, to come close even. But time to prepare can be a huge benefit. To read and read and read the play closely. To encounter it at different times and moods. And to wonder about it and just keep wondering. To decide nothing. To make no choices. To listen patiently to the piece and oneself—body and memory. When the play is vital and goes to deep places in our understanding and behavior it annihilates cliches. Its water must run deeper and lower into the actor’s body. This can take a bit of time when the body is partly or mostly bound with fear and tension and lies. As many adult bodies are. Much of the time. I was fortunate to have more than three months before rehearsals began to read and read and read the play. I worked steadily. I wondered about everything. The title, stage directions, names, biography, etc., etc., anything and everything, all of it was available to run into me and seek its depth. I felt the play’s careful construction and what it contains beyond the central drama of Alma and John, their sexual connection and incongruity. Will they or won’t they. And then what? In the script, Williams suggests a “great expanse of sky” in the design that will show space and time. The colors of day and evening and constellations at night—even the Milky Way. John tells Alma about general relativity and the Magellanic clouds and I wondered if Tennessee might be onto something about our existence as particles which apparently can be connected across huge distances and how John and Alma know the wonder and the terror of this. Like this, I kept on wondering.

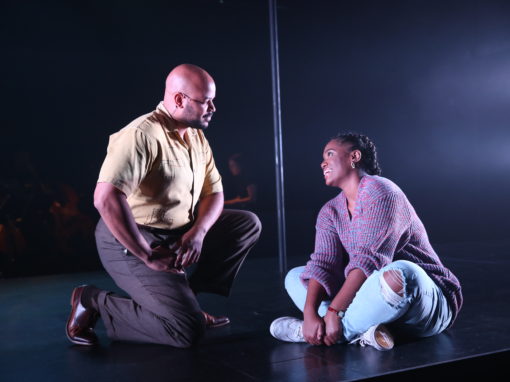

3. We Rehearse

Tough to report on the process of rehearsing something. It is a very tender and very special time. It’s a try this way and then one that way. Feeling nervous and vulnerable and so, so, so privileged. And it is a private time. It should mostly stay that way, I think. A couple things though. We were led with love and compassion and humor. The actors were all real professional artists. And experienced and brave enough to wonder about everything and to care for one another as they took on the particular challenges of their roles. I knew of Marin’s gifts. I got to know of her courage. We all did. Jack didn’t give us any props. Glorious Hill, Mississippi with no handkerchiefs? A doctor with no stethoscope? A hedonist with no applejack brandy flask? We went with it. In fact, it was singular and beautiful. A discovery. A great composer. Smart and sensitive designers. I thought Dane Laffrey’s set was magic. It was not Tennessee’s Milky Way, but it was Eternity.

4. Then What Happened

Rosemarie Tichler was the casting director and artistic producer at The Public Theater for more than a few heady years. She was also my teacher as I prepared to enter the profession. I always felt her support. Early on I suspected our tastes in acting tended in the same direction. She would push me hard and root for me harder. Years after that when I came back to New York for my second try at the business here, I reached out to her, and she helped get me auditions and met me more than a few times to listen to my woes and cheer me on some more. Early on opening night I spotted her. Front row. Edge of her chair—full attention on the action. As the evening went on, I felt her heart and her spirit expand as she rooted for me and everybody in the room. More, I think she was rooting for the practice of theater in her community. And on that night, we were all running up the score. It does feel slightly embarrassing to write such a thing about a piece of work I had a significant part in making. But only slightly. The rest of me is fully unembarrassed to recall and report on what I know to have been a successful event of live, poetic storytelling. I have known it as a performer and as part of an audience before on other occasions. More than a few, in fact. It is rare. But it is not once in a lifetime. I understand it like this: The play and the actors and the production begin to deliver, through presence and work and love, successive and intensifying moments of genuine interest. This becomes a gathered and sustained line of attention that forms among everyone in proximity to the action. Along this line transmissions begin. They start to fire around the room quickly, randomly even, and they carry a density of experience and memory. The twinned attributes of need and imagination become palpable and available; suddenly fully possessed and fully shared. And then it’s like the presence of a new being is felt and somehow, in every instant, countless stories are told and heard. It sounds ridiculous and like hooey to me even as I write about it. But I know that it is not. Really, it is something very simple and natural—and knowable. It is the sum of us all. And there is more. Yes, that sum knows something always that we, on our own, mostly forget—that the spirit is cleansed in an instant. Tennessee and Alma and John and Rosa and Mrs. Winemiller and Hamlet and You and Me live desperately, every second, in proximity to this truth. When we get close enough to know it for an instant or even just to recall our belief in its potential, well … that is a very good day on the job. Or in the theater. Or both. Haha.

So do take a break and go on the internet from time to time. Occasionally (constantly) I fantasize about having a death bed at some point and being conscious and wondering what I will decide to remember. When I do, I always think of working on this play with the folks who did it and the way we did it and I get seriously happy. So, thanks Jack. (Thank you internet too … haha) Since I was about fourteen I have been acquainted with the intense happy-sad of a play’s closing. This one was like a high school heartbreak. A constant ache in the chest for months that would flare on occasion and arrest me in a kind of catatonia. I’ll take it. If you saw the production—I don’t mean this in a creepy way—but I consider us connected forever. If you didn’t—I’m sorry. You missed a real one. But I love you anyway.

And I’m still kinda mad at you.

Haha.

Be good.

About the author:

Nathan Darrow has acted professionally for nearly twenty years. His experience ranges through stage and film, across the United States and internationally. In 2011 he was a part of The Bridge Project company, a group of twenty actors, ten from the U.K. and ten from the U.S.. Led by celebrated director of stage and film, Sam Mendes and actor-manager Kevin Spacey, the company built a production of Richard III which played at The Old Vic, BAM, and eight world cities on an international tour. With the Heart of America Shakespeare festival in his hometown

of Kansas City, Nathan has played Henry V, Romeo, and Hamlet. In 2018 he was John Buchanan, Jr. in CSC/Transport Group’s acclaimed production of Summer and Smoke. For three seasons he played Edward Meechum on Netflix’s flagship series House of Cards. In 2017 he played Andrew Madoff alongside Robert DeNiro and Michelle Pfeiffer in The Wizard of Liesfor HBO directed by Barry Levinson. Other screen credits include Gotham, Preacher, Rectify, Godless, and trader Mick Danzig on Showtime’sBillions. Nathan trained at NYU’s Graduate Acting Program under the guidance of Zelda Fichandler, Ron Van Lieu, and Liviu Ciulei. Since 2012 Nathan has been a company member of The Actors’ Center in NYC where he has deepened his understanding and practice of the art of acting principally under the guidance of Slava Dolgachev of Moscow’s New Drama Theater.

Explore Our Past Shows