I Need This Job Like I Need a Hole in My Head // by Jack Cummings III

Director Jack Cummings III goes toe to toe with an unforgettable actress.

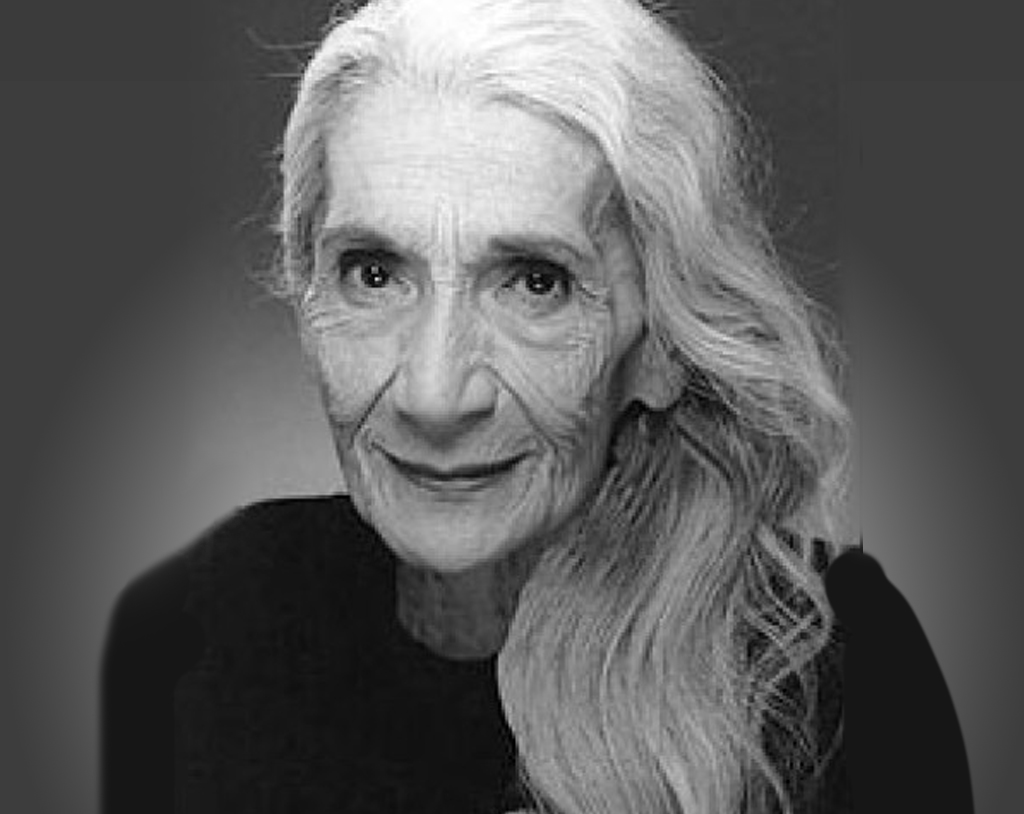

One of the many gifts of being a director is getting to work closely with actors. And occasionally, if you’re lucky, you meet an actor who truly defies expectation. For me, her name was Irma St. Paule.

The year was 2006 and we were doing a revival of Tad Mosel’s All The Way Home. In the play, there is a character named Great-Great-Granmaw who is stated to be 104 years old. She has no lines but in her one scene, her presence steers the play emotionally onto a course from which it never looks back. I knew finding an actress to play this role was going to be tricky. I came across Irma’s headshot in my files and immediately believed here was a woman who could actually be 104 (that’s how old she looked). I showed it to Nora Brennan, my casting director, and said, “This lady’s probably dead but let’s just see if her phone number still works.” Nora looked at me and dryly said, “No need to do that, she submitted herself.”

Irma accepted the role of Great-Great-Granmaw on the spot but then later became cranky when she realized she had no lines, demanding I add lines for her. I attempted to explain that this play was written in 1960, had won The Pulitzer Prize, and that her entire scene was built around the single fact that the character no longer possesses the power of speech. She vaguely accepted what I said. Vaguely.

A few days before the first rehearsal, I called Irma just to make sure everything was on track. She was irritated to hear from me and again started to give me the business about having no lines, threatening for the umpteenth time not to do the show. Her crankiness was now starting to wear on me and so I barked back with aggravated exasperation, to put it diplomatically. She sighed, took a pause, and said defeatedly, “Is there any way I can get out of this? I need this job like I need a hole in my head.” “No,” I replied quietly, “I need you to do this show.” She begrudgingly took down the address of the rehearsal space and promptly hung up on me.

I was relieved to see Irma walk through the door at the first rehearsal. We all went around the table and introduced ourselves. When it was Irma’s turn, she proclaimed bitterly to the entire room, “I’m the lady with no lines and I’m not sure I’m going to be doing this—I’ll let you know in a few days.” After an extremely awkward pause, the next person bravely introduced themselves and we moved on. Miraculously, I was able to convince Irma to keep showing up. With each rehearsal, I could see it dawning on her the potential power of her scene.

Upon arriving at the theatre for tech, she informed me that she couldn’t use the dressing rooms downstairs because she couldn’t go down “those stairs.” She said “those stairs” as if they were some old relative who had once betrayed her. I said that was okay and that we would set her up backstage. Out of sheer curiosity, I asked her how she handled the stairs in her apartment building since I knew for a fact that she lived in a fifth-floor walk-up. She said, “Once a day darling, once a day.” I looked at her puzzled. She then explained that she only made the trip up and down those five flights once a day—on all fours—when nobody else was around. I was speechless.

Later that week at a run-through, Ellen Weiss, who composed music for the show, said to me after her scene, “Irma needs her own entrance music” and proceeded to compose it on the spot. I feel at least once in a career, every actor should have their own entrance music.

A few months after we closed, Irma became ill and ended up at St. Vincent’s. I went to visit her and was relieved to see that despite being sick, she was still her feisty Slavic self. For the first time, I told her exactly how I felt about her: how much I admired her and that she was the secret reason our show worked. She waved her hand at me impatiently and began to argue that it wasn’t her but the young boy who played the lead – she referred to him as “that damn kid.” I waited patiently until she was done and said, “No, it was indeed you.” She then turned to me and said, “I love you.” I said, “I love you too, Irma.” Two days later, Irma died.

Ironically, despite having no lines, Irma walked away with the reviews. One memorable review said that during her scene, the audience “was so hushed the sound of angels’ wings could almost be heard in the auditorium.

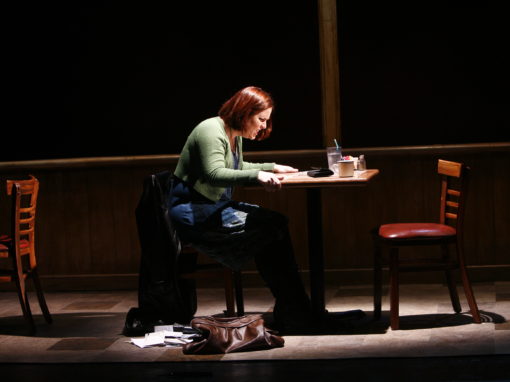

About Irma:

Explore Our Past Shows