A Spotlight for the Soul // Featuring Mary Testa

Legendary actor Mary Testa ruminates on starring in LaChiusa’s QUEEN OF THE MIST: a once-in-a-career experience.

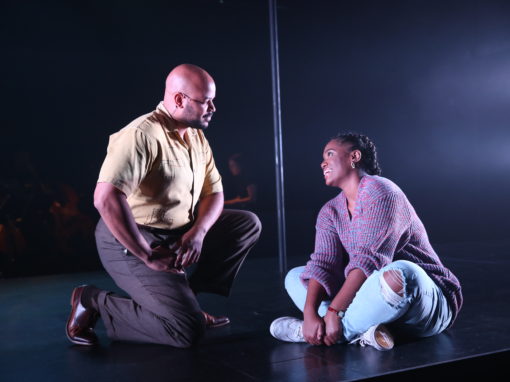

A note from Artistic Director Jack Cummings III: This week’s “While We’re Home” essay is a transcribed conversation I had the pleasure of having with my dear friend and frequent collaborator of nearly twenty years, Mary Testa. In this conversation you will hear about Mary’s path as one of our most important artists in the New York theatrical landscape, culminating with her iconic performance in our 2011 production of Michael John LaChiusa’s QUEEN OF THE MIST.

JACK: All right. So, my first question is, why the hell wouldn’t you just write an essay like I asked?

MARY: Because I feel I have nothing to say. I don’t. I could maybe come up with seven sentences. But you’re talking, like, 500 words or something. And I literally go blank.

JACK: You’ve never had a lack of something to say.

MARY: I know. But it’s a different story, writing, for me. I’m terrible at the art of sitting down and writing anything. And so, I can’t.

JACK: All right. I accept it. Let’s talk about how far we go back.

MARY: Yeah. That’s fine.

JACK: You probably don’t remember this. But I remember meeting you for the first time. And it was when I was engaged to Barbara. I think it was probably somewhere in 1996. Before we were married, actually. And do you remember Sam’s, that restaurant?

MARY: Yeah, I totally remember this. And I remember seeing her engagement ring and saying, “Oh my God, that’s beautiful.” And I’m sure I remember meeting you there.

JACK: I didn’t know anybody or anything. But I remember she was doing Big at The Shubert, and you were doing A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum with Nathan Lane.

MARY: Right.

JACK: And then I remember—when we started Transport Group, Robyn and I sent out our first fundraising letter. And I remember you sent back a donation, which I was very touched by.

MARY: Did I?

JACK: You were literally among the first batch of people that—

MARY: Oh, that’s nice. I don’t remember that at all.

JACK: And then you did our first gala. Our very first gala.

MARY: I did?

JACK: The one—the one that was—

MARY: Oh, the one that was like, eight hours long.

JACK: Yeah. That one. [LAUGHTER] I didn’t know what I was doing. And then First Lady Suite, in which you played Lorena Hickok, by Michael John LaChiusa. I probably contacted you in the late fall of 2003. That was our third show ever. We produced it in the spring of 2004.

MARY: What was your first show?

JACK: Our Town.

MARY: Okay.

JACK: But I remember calling you, and everyone else in that amazing cast—when I look back—I was operating on pure instinct and desperation. And technically, in terms of Equity, we were a showcase then. Which means you just do it for subway fare. And you each got a whopping $200. For the whole thing.

MARY: Right.

JACK: So, one of my questions is, what compels you to take such a chance? Someone you’ve never worked with. A company that has just started. For $200. In the East Village. When you obviously have worked in higher paying, more established venues, whether they be Broadway or off-Broadway. What in you says—because a lot of artists would say, “Are you insane? What are you doing?” You know?

MARY: I’ve always done this. It is taste. And if it’s an interesting project—and I love the Village and the East Village. And I love downtown theatre and had done a lot of downtown theatre. It was—of course! And then of course the group of people, there was no question. I mean, why would you say no to that? Now if you said, “Let’s do Les Miz in a theater on East 4thth Street,” I would say, “No thank you.”

JACK: For you, the material drives everything.

MARY: The material and the circumstance. I mean you can’t do those kinds of shows that only pay $200 for the whole thing all the time.

JACK: Of course.

MARY: You can do them once, every now and again. And you should do them every now and again. And then who—none of us knew that it was going to turn into what it turned into.

JACK: That group of women was just—

MARY: Extraordinary. I remember rehearsals with you — this is one of my favorite memories. The Musical Director—

JACK: Mary-Mitchell Campbell.

MARY: The best. She and I had gone through the whole show together, so I sort of knew what I was doing. I wasn’t totally off-book, but I knew what it was. And then we started working, and you would stop me every couple of lines. And I remember saying to you, “Jack! You can change anything you want, but you cannot keep stopping me. You have got to let me work through it as a whole piece for me. And then you can change it as many times as you want. But I cannot learn it this way.” Remember? Do you remember that?

JACK: [LAUGHTER] Yes. I remember that. And it was next to a moment where I just wanted to talk about something, or dissect it forever, which I am known to do. And you were like, “Ayayay, enough talking. Can we just do it?”

MARY: Yeah. Because I would rather do it. And then talk about what we just did, rather than chat about it forever.

JACK: That’s fair enough.

MARY: That’s my memory of you. And then you were like, “Oh, okay.” And then we sort of got on the same page, as far as how to do this. And then we did.

JACK: I remember just agreeing with you in that second. See, that—I was raised by a strong group of women growing up. And I know when to be, “Yep. Okay.” Also, back then I was a younger director, obviously. But it was my first time working on a Michael John show. And you had much more experience with it than I did. And, you know, he’s a very complicated, deep writer. These are not pages of a script that you do drive-bys on. With this incredible group of women who all had huge careers, I probably was being overly careful about just wanting to get it right, you know?

MARY: Sure.

JACK: Then I remember coming across a book by a woman named Joan Murray, called Queen of the Mist. It was a semi-fictional account of Anna Edson Taylor, the first person to go over Niagara Fall in a barrel in 1901. And I loved the book. And I sent it to you and Michael John, “What if we could adapt this into a musical for both of you?”

MARY: Yep.

JACK: What was your reaction to that? Because you had a very specific reaction I recall.

MARY: I read it, and I literally cried for three days. And I was never able to say, “It’s because of this, this, this and this.” There was just something in that story that my soul understood.

JACK: Do you have any insight into—17 years later—what that might be?

MARY: I think maybe because she was the underdog. And I was always used to being the underdog, kind of. And she was, in her way, a truthteller, even though she lied all the time. But in her own way, she expressed truthfully how she felt all the time. Even though sometimes, like I said, it was a lie. I think it was just a soul match.

JACK: Yeah. Michael John had a similar reaction. You know, he had a deep reaction, too, I remember.

MARY: Well, I think he’s been an underdog as well.

JACK: Right. I mean, I’ve always felt like one, definitely.

MARY: I think that was it. It was just so beautiful and an impossible story.

JACK: I remember when we went over to Michael John’s apartment, and he played through it for us for the first time. I have very distinct memories of that—of not only hearing the score, but of watching the two of you and your reaction to it, especially.

MARY: I just remember when he finished playing, I put my head down on the table and started sobbing again. It’s all about sobbing with that. Any time anybody asks me about it, I get—I get—I can just—I could just start to cry. And I cannot tell you definitely why. I don’t know what it is. I’m sure I’m not, like, a reincarnated Annie Taylor.

JACK: No, no, no.

MARY: But there’s something that’s so deep, that so deeply affects me about it.

JACK: For me, it was—I cannot imagine doing something as scary as she did.

MARY: No.

JACK: And I can’t imagine what life position she was in. Obviously, she needed money. She was alone, old, “old” in those days, and destitute. In many ways she had nowhere to go. And felt this was her only option. And then to do it, but after accomplishing it— still not get what you want from it.

MARY: Right. And have the capability and the brains to be able to design something herself that ultimately kept her safe, except for when they tried to get the lid off and hit it with an axe.

JACK: Right.

MARY: And in that time, being a woman who nobody gives a shit about.

JACK: Yeah. You become invisible. I mean, that’s the tragedy—

MARY: Totally.

JACK:—of misogyny in this culture. Is that once women hit a certain age, they become—

MARY: Yeah. Nothing’s changed. Nothing’s changed.

JACK: Also, she died a very sad death. She died alone in poverty and was put into an unmarked grave that they found later. I always feel a compulsion to kind of stand up for those people.

MARY: Exactly. How many people are there, you know what I mean? How many people are there in the world that are capable of so many things, but never got on a track or never had the opportunity, or whatever, that we don’t know about, that could have changed the world? Or could have changed things. I mean, imagine if she was harnessed and supported. That kind of mind. You know, could have done great things.

JACK: I agree. You know, one of the things that grabbed me about the story was that she was the first person, man or woman, to do it—but then because a year later a man copied her method and did it successfully as well, the sexist culture then assumed he was the first person, as well.

MARY: Exactly. She was completely forgotten. And made fun of. Mocked. And I understand all of that stuff as a woman, and being a woman who is not—how do I put this? I’m not a girly girl. I don’t hide my strength. That has been the source of a lot of derision in my life, you know what I mean? So, I understand that as well. And if she had been a beautiful woman, she would have gotten away with more.

JACK: Well, there would have been no question. I also felt— for me, I felt it was important to tell a woman’s story, where there was no romantic storyline.

MARY: Right.

JACK: You know? That a woman’s existence is more than just being in a romance. Romance is fine. But you know. That was always something that kind of grabbed me.

MARY: Me too.

JACK: Let’s talk a little bit about your relationship with Michael John. You all have collaborated on many, many shows over the years.

MARY: About five. I think I’ve done five of his shows.

JACK: Five. That’s a lot, by a contemporary composer.

MARY: Yeah.

JACK: What about his authorial voice, as a lyricist, book-writer, and composer—because he does all three sometimes—what do you respond to?

MARY: As an actor, anything that you need is in the music. It’s like a map for you.

JACK: Agreed.

MARY: Which I find extraordinary, that—especially the women’s roles that Michael John can write. He writes women’s roles like nobody. You know? And I also think I connect with him tribally. I totally connect with him as an Italian.

JACK: So, you feel there’s a—you feel there’s just a pure emotional temperament you both share?

MARY: Yeah. You know, Queen of the Mist, vocally, is a fucking bitch.

JACK: Yes.

MARY: Did he have to make it as much of a bitch? I don’t know. You know what I mean?

JACK: I would say—I would say on that, I remember talking to him about that. Not about, like, “Hey, this seems hard for Mary,” because to the people rehearsing with you, you pretty much always seem effortless. Which does not mean that inside it is effortless. But it always appears that way. So, I don’t know necessarily to question that unless you would say it. But I do remember that he did want to—I will defend him on this—I remember that he did want to challenge you. He wanted to push you a little bit. Because he wanted you to be great. He wanted the world to see—he didn’t want any stone left unturned—the fullest of Mary Testa.

MARY: I get it. I’m not saying he did it in a mean way. If he’s gonna do something for you, he is definitely gonna challenge you. The thing with Michael John’s music is it goes places you don’t expect, but yet it makes perfect sense. Like, I can’t tell you how many shows I’ve sat through where I’m able to sing along to music I don’t know, because I know exactly where it’s gonna go. I know which chord is coming next. And I’m not interested in that. I like the surprise and the—the odder kind of—you know, the more intensely different. And to me, that’s what Michael John is. And he can write in all kinds of styles. But his voice is deep and different and challenging. And I—that’s what I like. And I like difficult. I don’t like easy melodic—not that he’s not melodic. I think he’s incredibly melodic. When people complain, “I can’t—you can’t sing along. I just don’t know.” I’m just like, “You’re stupid. You’re just stupid, then. You’re stupid, and that’s all there is to it.”

JACK: I remember a year after First Lady Suite, and we did the concert of that show at The New York Historical Society. And Audra was filling in for Sherry Boone. She and I were talking. We were talking about the difficulty of his music. And she was saying, “You know, I find”—and I thought this was an interesting point, “I find it actually easy to learn, because it is so distinct and so only his voice, that it stays in your brain, because it’s so singular.”

MARY: I agree. I remember learning—the most difficult things I’ve learned of Michael John’s were the choral parts in Marie Christine.

JACK: Oh, God.

MARY: They were incredibly hard. But once you got them, they were thrilling. It fit together like a fucking tapestry. And you never sang it wrong again, because it was like, it was calling you, this clarion voice, to just—it was exquisite and thrilling.

JACK: Here’s what I want to talk about, that I find—no one ever talks about this. And I’m gonna use cliches within our industry, or terms that I don’t necessarily agree with. But I’m just going to use them for a shorthand.

MARY: Okay.

JACK: Just so we can have a conversation. All right. So, if you are Mary Testa, and all the people that have similar careers, right? Or similar paths, in terms of the types of role that they play. So, for shorthand’s sake, we’re gonna call them supporting roles or featured roles or character roles.

MARY: Sure.

JACK: Meaning that, one is not carrying the show on one’s back. What are your feelings about that? Have you been fine with that? Because you’ve played some great—a great role is a great role, obviously.

MARY: Right. Well, yes, I suppose I’ve been fine with it. The character roles are always way more interesting. But I can’t understand why there’s that thing where there’s the character actor and then the leading people. The leading people always get, you know, every song. And I just never understood why that had to be that way. I remember saying to my agent, when I was really—a long, long time ago, “Why can’t they make a soap opera with real-looking people, in real situations?” And he said to me, “Because, Mary, nobody would care about that. Because everybody’s living that. They only want to see the fantasy of the beautiful people, and all of that.” And I thought, “Okay. I’ll accept that.” But it just—I don’t get it. When I was in my 20s, I was competing with women in their 40s for roles. I knew that it wasn’t gonna be until I was in my 40s, that I was really gonna start to work proper. I always worked. But that—you know, the roles would fit better, in a way.

JACK: And to be very frank about it, in terms of the superficiality of our business, do you find—is it as plain as saying that the reason you were competing for those roles for women in their 40s when you were 20, is because you don’t look like—and I’m just using this name as an example—Kelli O’Hara.

MARY: Right.

JACK: I mean, this is the history of the world, right? There’s a superficiality based on what we consider traditional looks to be, and how they’re valued. Right? And I know it’s in every segment of society.

MARY: And it’s still happening. It’s never changed. And I don’t think it will change. That’s why Queen of the Mist was so special for me. Because I was it. The lead. For the first time.

JACK: What was interesting though is Anna Taylor is basically the character role.

MARY: But as the lead.

JACK: Yes. In another musical, her character would have been the character/supporting part.

MARY: To me, that’s way more interesting than most of the shit that’s—you know. The classic way that things are done a lot of the time.

JACK: A lot.

MARY: Yeah.

JACK: And in this pandemic, we’re all in this particular moment of starting to unpack many things that we were always taught and thinking, “Hey—what was that bill of goods we were being sold and buying over and over again?” I’m hoping that maybe we can all come out of this with the attitude, “Let’s not immediately accept everything we’ve been told.”

MARY: Don’t—don’t hold your breath. Because as soon as things return to normal, people will go back to the same old bullshit.

JACK: That’s all of our fears. And so, why do you think—

MARY: Before you continue with your question, let me just say that—

JACK: I don’t know if I had one. I might have been just rambling.

MARY: I’ve never been a person with a plan. I never was the person who moved to New York and said, “I’m gonna give myself five years. If I haven’t made it in five years, then I’m gonna go somewhere else.” I never thought that way. And I don’t have a plan. Whatever falls in front of me, I do. Not everything—I’ve turned down things that don’t interest me. But basically, I’m like a pinball. I get shot, and whatever I hit up against, I deal with.

JACK: Okay.

MARY: The only reason that we have a career to talk about here is because I’ve been doing it for 45 years. I don’t know—I guess it’s been successful. I’ve made a living as an actor. And I’ve been—you know, lauded with—what do you call ‘em—nominations for things. Which is really nice. But I don’t have the brain or the capability of plotting out a more successful career. I just don’t have that. I don’t have the star mentality. I just have the “I want to be an actor” mentality.

JACK: But I would say that—maybe it’s not a plan. But one thing from the outside watching and hearing you talk about your experiences, one thing you definitely— and I’d love for you to talk about— you do have a loyalty and a passion for new work. And that is not always the case with everyone. Because with new work comes big risk.

MARY: Yeah.

JACK: And it’s one thing to do a revival of The King and I. It is another thing to say, “Here’s this new or not-so-new composer, trying something new—here goes nothing!” Right? So, it seems to me that if you had a plan, your plan was, “Well, here’s one thing I’m gonna live by—which is, when in doubt, I’m gonna choose to take a chance on the new. As opposed to relying on the old.” Would that be fair?

MARY: I think that would be fair, yeah. But how I am as an artist, is how I am as a person. I am a very loyal person, as well. And I am a person that likes new ideas. That’s who I am. Period.

JACK: In the end, you’re just being true to yourself?

MARY: I think so. Also, at this stage of the game—I realize too how much you really just don’t know. You just don’t know anything. And so, all you can do—I’m realizing this—is be truthful. Is find the truth, in the lines, in the music.

JACK: So, here you are. Playing Anna. Now you’re the lead. This will be your biggest role.

MARY: Yes.

JACK: Which is a different category. I mean, I’ve directed shows where there are leads before. But just so for the reader this is clear, this was a lead that never left stage except for one—three-minute song that Julia Murney had in the second act? That was your only time where you got to leave stage.

MARY: Yes.

JACK: So, I’m just curious from a stamina point of view, did that ever daunt you?

MARY: No. Because—no. But when it was all over, and I—we did, what, 50-some odd shows? I was exhausted. I think that the idea of, like, you know—like, when something is convex, and then it turns concave. That doing something on stage that is unstoppable, in a way, was so wonderful. I could just be as big as I wanted to be. I could just go as far as I wanted to go, doing that part. I never thought, “Oh my God, I’ve got to push through this.” It was all-encompassing.

JACK: A thrilling ride of adrenaline in some way?

MARY: Yes, totally. And to just have that group of people around to work with and be with. Everybody is good, and in it for the art. And wanting to tell the story as purely and greatly as possible. That’s the most exquisite thing. That doesn’t drag you down. That energizes you.

JACK: It helps lift you up.

MARY: Yeah. I would like to always play the lead.

JACK: What do you think the show—the role and the show, as a piece of art, is trying to say? Or what does it say to you?

MARY: You know, in retrospect, I don’t think I thought of it then, but I think that it’s a cautionary tale, in a way. Of humankind. And value. And who we value and who we don’t. And—the folly of human—you know, who we value.

JACK: Yeah.

MARY: I think as a race, we are so focused on what we think shines, that we miss a whole bunch of stuff. This is in retrospect. I wouldn’t have told you this when we did it.

JACK: People get thrown away. For sure. They’re discarded.

MARY: Totally. And—I mean, there are people thrown away everywhere you look. It’s—what brain does that guy who’s been sleeping outside, what brain does he have? So, it’s that for me, now.

JACK: I have a memory that I want you to talk about, and I’ll throw in my two cents first. I remember we were all in rehearsal. Somehow, we were talking about the curtain call. It was probably late in the game because I always forget about them. And I remember you were gonna take the last bow, obviously. And it came up that you had never taken the last bow. And I said, “Well, maybe not on Broadway. But you’ve taken the last bow before.” And you said, “No.” And I kept going because I was thinking, “She’s just not remembering everything.” And I said, “Okay. But in dinner theater, right?” “No.” “College?” “No.” “High school?” “No.” “Junior high?” “No.” “Summer camp?” And you just kept repeating “No” over and over and over. And I said, “You mean to tell me that”—

MARY: First of all, I never did theater in junior high. I never went to summer camp. And I never did dinner theater.

JACK: But I mean it was amazing to me. Because most—90 percent of professional actors, somewhere, have played a lead who takes the last bow. Whether it was community theater, or somewhere. And I remember taking the subway home with Michael John because we live near each other. And he turned to me and said, “We’ve got to give her a great curtain call.” And I nodded and said, “I know.” He said, “I’m gonna write the curtain”—because he hadn’t written the curtain call music yet—“and I’ll write it in that way, where, you know, there’s a lead-up and a build and then it bursts with her theme when she comes out.” You know, those grand curtain calls that we all love, actually. I love those kinds of curtain calls. And then when we did it at the first preview, everyone in the cast knew that this was the first time you were taking the last bow and they were all very emotional about it, watching you take it.

MARY: I cried every single time. Because if the audience wasn’t standing already, they stood when I came out. I’m crying now. That was so moving to me. Always.

JACK: Why do you think—why is that meaningful to an actor? I mean, can we talk about it?

MARY: I honestly don’t know. I guess it’s because if you’ve never had it, when you get it, it’s overwhelming. My experience in bows—I mean, I get a fair amount of applause, usually and that’s all great. But my experience in bows was always, when there’s the final bow with everybody, coming downstage generally, and bowing. When I look at the audience, no one is ever looking at me. They’re always looking at the people in the center. Always. And there’s a part of me that can never understand why at least one person isn’t looking at me. I guess that’s the “Look at me! Look at me!” Right?

JACK: It made you feel like you matter. Right?

MARY: Yeah.

JACK: And then another memory I have that—I like to think that you felt this. I remember there was a spoken and unspoken thing around anyone who worked on this show, that this is for Mary. This is her moment. We’re here for the work, we’re here for the story, we’re here for Michael John of course. But we are here for Mary. You know? As much as anyone else. I remember Julia telling me that a big reason she did the show was that she felt Mary Testa has spent a career supporting other actors onstage. And so, it is time that we show up to support her.

MARY: Well, that’s Julia. She’s just—very special.

JACK: I was very moved by that.

JACK: And I felt those actors, all the actors in that company—they loved doing it. I think they felt it was a gift to be able to surround you.

MARY: That’s unbelievable and so incredibly moving to me. Everybody in that company was exquisite.

JACK: We felt lucky. We were witnessing a once-in-a-lifetime performance, absolutely.

MARY: I don’t know that I’ll ever have something like that again. And I’ll tell you, I could do that show easily again.

JACK: One final memory that I have—of hearing about as I wasn’t there—was when your Dad came to the show.

MARY: Oh my God. Oh, this is gonna make me cry. My Dad was very moved by it. And, you know, he saw all kinds of things. He was always proud. He would very much always say, “Why didn’t they let you play the lead?” You know, like that type of person. But our curtain call was on counts. And my father was in the front row. And he just got up.

JACK: Which, just to be clear, he was in the front row, which was the same level as the stage, because of the way we did it.

MARY: Yeah. It was at the Judson Gym. And he just put his arm—he put his arms out and he—there were tears in his eyes. And he said, “I’m so proud of you.” It was unbelievable. And I was trying to honor him, but also say, “Dad, I gotta do this curtain call.” So, I think I just laughed and cried at the same time. But. I just—

JACK: But he got up, right? Didn’t he actually get up out of his seat?

MARY: Yes, he got up. And he had his arms opened. And he came to me over to me. And he was—but he had tears in his eyes. Oh my God, Jack. [EMOTIONAL]

JACK: I was on my way to the theater, and people called me to tell me about this. When I got there, everyone in the company came over to me and said, “You missed the most amazing moment we’ve ever witnessed.”

MARY: [CRYING] Yes.

JACK: Witnessing that love and interaction between a parent and a child.

MARY: He was so proud. My mother was gone, so my mother wasn’t there. I mean, I’ll never forget that. It was—it’s been—it’s incredibly amazing. I mean, I’m like, sobbing over here. Because, you know, my Dad is gone. So. You know.

JACK: Right. Right. I remember saying to myself, “Well, if we only did this show for that moment, then I’m good with that.”

MARY: I know. We’ve done our jobs.

JACK: I think we can rest easy.

MARY: The whole experience was exquisite. I’m so—that’s—Queen of the Mist will always be the highest point of my career. The highest. No matter what I do. You know. Maybe I’m done, who knows.

JACK: No, you’re not. You’re not done. You’re not done.

MARY: Maybe I’ll do a million different things. Maybe, maybe—you know. I will do a lot more work. But, you know, I think Queen of the Mist will always be it. The highest thing.

About Mary:

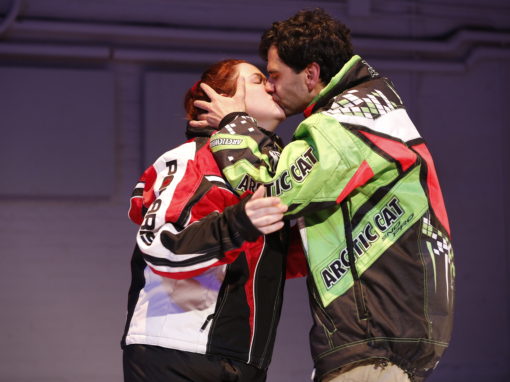

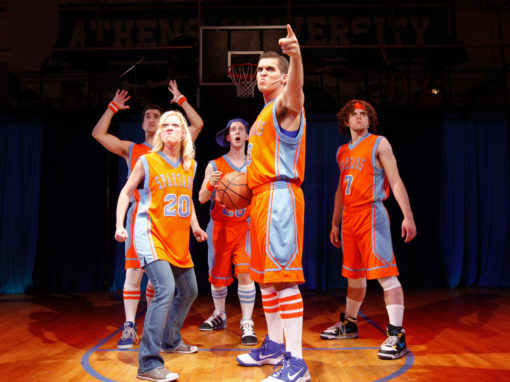

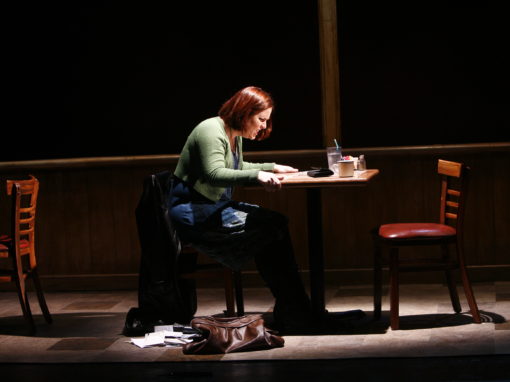

Explore Our Past Shows