Why Do I Go to the Theatre? // by Eamon Foley

A seasoned Broadway vet at the age of 11, young Eamon Foley ventures downtown and asks some big questions.

I was two Broadway shows deep when I was cast in Transport Group’s world premiere musical, The Audience. I was also eleven years old. I had just completed my Sondheim phase, having delivered life-changing performances as “newsboy” in Gypsy and “Billy” in Assassins, but like any mid-career artist, there’s a time to go downtown and be experimental. I’ll admit, the 200-something dollar one-time stipend didn’t thrill me, but I was here to work, not to bitch, and break barriers with my 45 castmates.

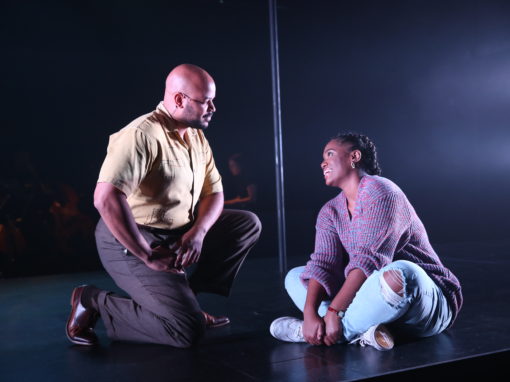

That’s right, a 46-person cast. It was a massive, chaotic undertaking led by a young Jack Cummings III (TG Artistic Director), who was up against an army of 46 disgruntled actors, all with egos that required stroking, all waiting for their lines or songs to come in from the 29 writers. Our cast sat in five rows of plush velvet seats pitched towards the (real) audience, and we sang our reactions to a fictional Broadway production reminiscent of Falsettos. Among others, our onstage audience had our four old Jews, a young gay couple, an old gay couple, the woman who brought her husband’s ashes to the theater (a transcendent Rita Gardner), the couple on their first date—all reacting to the show before us as it pertained to our lives. I played the son of a conservative family of four from Fort Worth, Texas (written by Yvonne Adrian), who did not know what they were getting into when they were hawked these tickets.

The script we received on our first day of rehearsals was a 200-page Frankenstein-job, patching the work together of the many writers. “Are we being punk’d?” asked one of the cast members. Gripes and grumbles quietly reverberated in the corners of the rehearsal hall. I found in my early years in the theater that adults like to pretend kids don’t hear and absorb absolutely everything being said around them. On this show I didn’t have a friend my age to consort with, so all I could do was quietly observe. I played the quiet spy throughout the run, sharing a dressing room with the entirety of the male adult cast in the basement of The Connelly Theater, partitioned from the green room by a thin piece of duvateen. They rarely censored themselves as they spoke of their conquests, their diseases, or their frustrations with our union. Children will listen. I didn’t mind my role as the fly on the wall, catching slices of the adult experience that muggle children weren’t privy to. All that exposure acted as clues into my personhood. And the content of the musical would go on to do the same.

I remember sitting in the second row of folding chairs in rehearsal and staring at Jack as he faced the wrath of a confused cast just thinking, “That poor man.” But the project had heart, the vision was clear, and as it started to form, the trust started to grow. The script condensed into the essential. Songs came and went to the chagrin of some cast members and the relief of others. This cast wasn’t particularly cagey with how they felt about the material. But as we moved forward, the reason for each character’s existence solidified around how they spoke to the central question of the piece: “Why do we go to the theater? What purpose does it serve?” (the words of lyricist Mark Campbell from our opening number)

I didn’t know why I was so drawn to the theater. All I knew was that it was the only place I felt pride. I was a gangly little queer kid. The sibilant “s” gave me away from the get-go. I wasn’t coordinated with ball sports. I was the teacher’s favorite. I preferred my lunch in the cool, quiet library, avoiding the deafening shriek of the cafeteria and the uncertainty of recess. But I could sing, and I could dance, and that’s where I found the praise I wasn’t finding on the soccer field. I was nine when I was cast in the 2003 Broadway revival of Gypsy and was surrounded by an overwhelming flood of warmth from the cast. They cheered me on as I lip-synced “Rose’s Turn” every night directly under Bernadette Peters in the ensemble men’s dressing room. They got it. They had all been that kid. But what was it about theater itself, beyond the familial aspect, that drew me in?

In The Audience, I didn’t have a whole lot to do except a short verse in the opening number and a few questions here and there about the gay going-ons in the fictional Falsettos we were watching. But it didn’t faze me. The main reason for working was to miss school, and I was achieving that. But then one day, I walked into rehearsal and was called to the front by Jack. A cast member I had worked with in the past, Rosemary Loar, had gone to bat for me to the team, saying that I had a killer voice, and I should have a song.

“I Like What I See” was written by Cheryl Stern (lyrics) and Tom Kochan (music). The song was about my character discovering theater for the first time and being moved by the raw emotion in front of him. This family in the fictional Falsettos, for all their flaws, was going through their drama loudly and bravely together, belting their thoughts and feelings to the rafters, contrasting the stilted way my character’s Texas family dealt with their grievances:

They seem to love and hate each other all at the same time.

They’re not afraid to feel that.

I feel that.

Is that a crime?

I felt that about my own family back in Connecticut. They loved me and supported me, but we couldn’t have been more different. My inability to connect with them over the basics led me to grow resentful, but I didn’t know how to voice this frustration brewing in me. If only I could have wailed a William Finn song at them to help them get it, or at least articulate that I didn’t feel gotten. Perhaps a healthy dialogue could have been opened. But instead, I just lived with a quiet discomfort, boarding the train for work to escape these lovely people and this lovely town that made me feel so uncomfortable.

The reviews were mostly glowing, but I’m an artist so I’m only going to focus on our one scathing review from Charles Isherwood, formerly of The New York Times. When speaking about our onstage family, he wrote, “A strait-laced husband and wife from out-of-town trade nervous glances at the shocking antics onstage… But their son doesn’t share their distaste. He sings a little epiphany titled ‘I Like What I See,’ hereby announcing a bid for future membership in the ever-renewing tribe of show queens.”

It wasn’t a gay role. I wasn’t meant to be a queen in any way. I was meant to be falling in love with theater, an asexual act. And yet here I was, eleven years old, being outed in The New York Times for my delivery of the material. My mom read the review cold off her phone before nervously stashing it away. The actor walking with us muttered, “That’s an interesting interpretation.” Shame overcame me. I was found out, and there it was in black and white. Thanks, Charlie.

But what was there really to be ashamed about? So, what if I brought my baby show queen into the role? I was embodying the truth of that song by serving a part of myself onstage with more ferocity and bravery than I could in my real life. The song was about how theater was, in a way, more honest than life. In performing the song, my truth shined through. I was more real and courageous during those three minutes than I was during any other part of my day.

It’s like real life, only faster.

And it means a whole lot more.

And though they’re living a disaster, it’s so much cooler to explore.

I want to live like them—I think I like it.

I like what I see.

This little boy I was portraying knew exactly why I drowned my ears in showtunes. I was addicted to the truth in the lie, and the fervor by which it was shared. If only real life could be so real.

During the pandemic I choreographed and shot a short music video at The Connelly Theater. At the time I couldn’t place why the space felt so familiar. The music video was entitled “Home,” about the theater as a home for showfolk. The sentiment of the music video is only heightened by “I Like What I See.” It’s not some great escape that keeps us coming back, but it’s how it exposes our rawest, most real selves. We come home to ourselves when we put our pretenses aside and subscribe to authenticity, even with stage lights blaring down at us and paint all over our faces. It’s a great paradox, sure, but more simply the theater gives us permission to feel, whether we are onstage or in the audience. And I’m still that little boy belting onstage about how “I want to live like them”—like those brave characters in plays and musicals. That’s why I come to the theater.

About the author:

Explore Our Past Shows