Telling Your Story to Heal // by Yvonne Adrian

Playwright Yvonne Adrian mines her soul and shares her family’s darkest moments to help find the light.

The years were 1996 to 2005.

In 1996, I was a member of Scott Elliot’s Playwrights Unit at The New Group Theatre Company. I was emotionally in bad shape. My 15-year-old daughter had just been diagnosed with anorexia, a deadly eating disorder. I became a desperate “mothering-disorder.” I was waking up in the middle of the night with 3 a.m. terrors. What to do? I wrote a 15-page diatribe-of-fear about myself and my family’s dilemma. We were splintered. I felt The Playwrights Unit was a safe place to expose myself. It stunned the group. No one spoke. Scott quietly leaned toward me and gave me notes. I was to rewrite the 15 pages of emotional incidents and turn them into scenes. I heard him say, “It’s a musical.” Now I’m the one who’s stunned. He told me he heard songs coming out of the scenes that would build to an even deeper emotional place. I was to go to work and bring in the first draft the next week. I did. I wrote a scene. I wrote a poem thinking it could be a song. It was really bad. Even I cringed. Scott introduced me to Cheryl Stern. She was a member of The New Group Actors Unit. We met. We clicked. We started writing. Scott insisted we needed to find a composer. Enter Tom Kochan, Cheryl’s husband. I felt blessed! We met at their place, reading, writing, and re-writing. And the journey began. I wrote monologues for Cheryl who turned my words into amazing lyrics. Tom would fit her lyrics and his music together perfectly. Tears flowed so many times. I realized I was the source for a story (mine!) that I was placing in their hands, and it was coming to life.

Our musical was first titled Vanity & Vexation (later changed to Nor’mal). Scott directed us in a reading of Vanity & Vexation at The John Houseman Theater. We cast Daisy Eagan as Polly (the daughter), Maureen Moore as Gayla (the mother), Peter Ratray as Robert (the father), and Devin Ratray as Zachary (the brother). But then everything changed when Scott’s first play, Ecstasy, became a huge hit. He had to let us go. I totally panicked. We needed a new director. Maureen Moore came to the rescue. She suggested Jack Cummings. Who? We met Jack. Afterwards, Cheryl, said, “Grab him!” We grabbed. He said yes. We got to know each other during meetings at Cheryl and Tom’s place. We went to work: reading, writing, and re-writing. We spent many writer/director retreats, away from the energy of New York, at my house in Staatsburg, NY near Rhinebeck. For meals, we would shop, chop, cook, and wash dishes together. We noticed Jack was only eating white foods and NO TOMATOES. Tom ate lots of carrots. Cheryl always brought tuna fish, white bread, and macaroni & cheese. I brought bananas and vanilla yogurt. While there, Jack told me to prepare for “the long haul” as I would have to sit at the computer and bleed. Umm. I pulled out my Sony Walkman and recorded our conversations. Back in New York, we prepared for the reading-writing-re-writing circuit, hoping for table reads at developmental theater companies. We were casting and re-casting brilliant New York theater talents. I shed tears during those times through every single reading.

Early in our development, we had written a song titled “Write This” based on a real-life moment I had with my daughter. By this point, she was in bad shape and deteriorating fast. I told her we were checking her into the hospital. She said, “No, I won’t go!” I said we would call the police, have her arrested, and the police would take her to the hospital. She said, “I’m old enough to check myself out in 72 hours.” I responded with, “And I’ll check you in every 72 hours!” Her response, “You’re in my room, Mother.” My response, “If you don’t go to the hospital, you’ll die.” She screamed at me, “I don’t care!” “I screamed, “Fine! Then just tell me what you want written on your tombstone!” I ran out of her room and down the hall. In our show’s development, this is where I had to write what Polly (the daughter) might have then said to herself–what would her tombstone say? I knew she was frightened by being teased and bullied at school. She wanted so badly to fit in. She was a sweet, kind person, but treated unkindly. Never would she say hurtful things to others, even when they were mean to her. She had a good heart. I continued to write down all of these thoughts I imagined going through Polly’s mind in that moment and handed them to Cheryl who then wrote these lyrics:

Write this,

Here lies a baby

Who struggled in her mother’s arms

Crying to be free.

Write this,

Here lies a little girl

who always tried so hard to be

the sweetest, kindest, prettiest

Miss Everything to everyone

A good girl – the best

Write this,

She failed the test.

Write this,

Here lies a young girl

Who found that there was good and bad

Raging deep within.

Write this,

Here lies a frightened child

Who only wanted to fit in.

She made the hardest, scariest

Of vain attempts to wage a war

With demons, unknown.

Write this,

She was alone.

After hearing the number, Jack immediately wanted to add Gayla, the mother’s response. He came to me and asked me to write what the mother would say—what would the mother write on her daughter’s tombstone? We needed her thoughts too. The thoughts were to be my own reaction, as if I knew what my daughter was writing. I had to dig deeply into my soul because it was to be written that moment. I did not want to go home and think about it. I had my list. I spoke of her birth and me holding her close, to see if she had 10 fingers and 10 toes—I wanted to know she was a normal and healthy baby. I knew she would not like Heaven, or all those angels flapping their white wings. No, she would not like that. She did not like white—she never wore white. Then the cast and creatives began improvising like crazy playing around with my words. And “Write This” was rewritten, now with the addition of the mother’s inner most thoughts, creating an emotional peak for the show we had been searching for.

The development circuit was long and arduous as they tend to be for new musicals. My most vivid memory during this time was a workshop at The Lark in their BareBones Development Series where the cast was finally on their feet. I named it, The Workshop From Hell. The audience was seated on both sides of the space, facing each other. That was weird. I thought Jack’s creative mind had gone haywire. He decided to use wooden folding chairs for the cast of seven to fold, pick up, push, pull, and slide around the small studio. That was really weird. He wanted to indicate change of environment. I wanted to run and find a new director. Cheryl and I sat together totally frozen in fear. What if someone fell, bumped their head, broke an ankle, landed on their knees or even worse? It was like watching dodge’em at a carnival. The 80-year-old actor playing Granny was directed to actually stand on a chair! I hear Cheryl muttering, “Oy vey, Oy vey, Oy vey!” The audience loved it. Standing ovation! We won The Jonathan Larson Award for our Lark workshop using charming wooden chairs.

A moment to share with the reader: I had lived all the moments I had written. I was re-living them all over again. My husband, Roger, went to Al-Anon meetings (he needed to vent, as this disease is addictive). Both of us attended eating disorder meetings with families, friends, or others like us. Our son felt totally dismissed. He is a songwriter, composer. He had a rock band playing gigs at downtown village clubs that welcomed teenage bands. We couldn’t show up. So, he was always pissed. When we had the opportunity for audience talkbacks after various presentations, it was devastating to hear how many mixes of all cultures suffered from this disease. I learned that most keep it a secret behind closed doors. Guilt was our connection, although we were told repeatedly, “It isn’t your fault.” From fathers, we heard “Why can’t she just eat”?” A well-known actor who played the father in one reading was rehearsing a speed-thru with us at Ripley-Grier. He left the studio on his lunch break, and I haven’t seen him since. I discovered how difficult it is for some men to understand why a teenager or anyone is unable to eat.

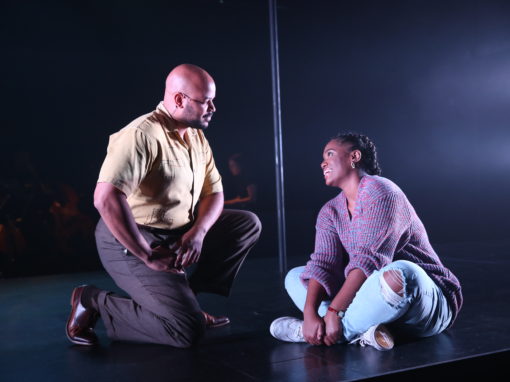

Cut to Staatsburg Retreat, 2005. We are only a few months away from the Transport Group production opening at The Connelly Theater. We are cast: Barbara Walsh as Gayla (the mother), Erin Leigh Peck as Polly (the daughter), Adam Heller as Robert (the father), and Nicholas Belton as Zachary (the brother). We are preparing the final moments of the show. We are seated at a small table, working on the very last scene when Polly is in the hospital and close to dying (the Gayla in me felt like dying every time I watched it in rehearsals). Jack intuitively knew two songs were missing. He leaned over the small table with papers scattered everywhere. I can still see him looking into my eyes. Ohhh. I’m thinking about that damn looong haaaul. I’m going to bleed again. Quickly, I clicked on my Sony Walkman. Quietly, he asked if I could tell him anything from the depth of my heart that might help me resolve my guilt. I felt guilty about being a mother and bringing a child into my world. I felt guilty for mistreating my son. I felt guilty for mistreating my husband. I felt guilty for the fights I had with my daughter. I was afraid I had said too many angry things to all of them. What would I change if I could? I choked. I took a breath and told Jack if only I could have one more chance, a second chance. I would ask for forgiveness. I could make up for all my wrongs. I could smile, even laugh again. I could hug my family, spend time having fun. Hopefully, I could go on with my life without remorse. Cheryl and Tom listened intently and then wrote “Second Chance,” a song for Gayla while she watches her daughter fight for her life—a mother’s cry for help. The final stanza especially always got to me:

If I had a second chance

Would I know the answers?

If I had a second chance

Would there be no shame?

If I had a second chance

Could I save you from me?

Could I just let you be?

Could I forgive myself?

Could you forgive me?

We continued our work. We still needed a final song to end the show. We did not want to write a happy Broadway ending. How do we write it and find the right words to sing? What did I want most now? How can I convey the beginning of healing without being sappy? I thought. I realized I just wanted a day when nothing happened. Just a normal day without conflict, strife, and crazy events. My family wanted to breathe again. A day like, “Let’s go for a Sunday drive—let’s enjoy looking out the window of the car at the vibrant fall leaves.” Just an ordinary day.

Final Staatsburg retreat: We are waiting to hear the final song. Usually, Tom would write a song overnight. But this time was different. This song had taken him a while. I will never forget this moment. Tom set up his recorder and speaker. I held my breath and tried not to show it. The music started. It was melodious and lovely. He sang the song to us, all by himself. No pre-recorded voices. No big fanfare. We cried. The show’s finale, “Just a Day” was born.

It was 3:04

On October third

When we walked her out

The hospital door

Just a day

Just an autumn day

Just a day

We got in the car

No one said a word

Zach took the wheel

No one slammed the door

Just a day

And we drove away

Just a day

And nothing fancy happened

I think we stopped for gas

And nobody had to do anything

We were content to let the minutes pass

Content to sit

Let the pieces fit back together

After the “long haul” reading-writing-re-writing, which had taken a revealing emotional toll on the experience of telling my story, I felt I finally had the strength to go on. I had survived. My son is speaking to me again. My husband and I have mended our relationship. My daughter has recovered and is well. She has an 18-year-old son entering his first year of college, graduating in 2025. Roger and I are blessed with three normal, healthy grandchildren.

[Author’s note: After the Transport Group world premiere of NOR’MAL, Robyn Hussa, Transport Group’s Co-Founder with Jack, created Nor’mal: In Schools Program (NIS). In Wisconsin, at Greendale High School, teacher/director Eric Christiansen directed an all-student production with some new material and a groundbreaking educational version of the show was born, helping thousands of high school students all over the country deal with the life-threatening issue of eating disorders/mental health which tragically affect hundreds of thousands of people each year.]

About the author:

Explore Our Past Shows