The Hairy Details // By Theresa McCarthy

Actor Theresa McCarthy embraces QUEEN OF THE MIST at a personal crossroads and finds unlikely inspiration.

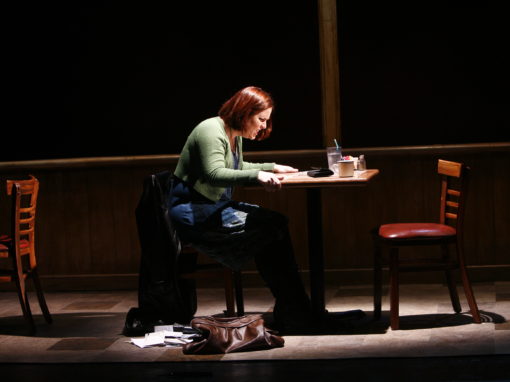

Rehearsals for Queen of the Mist begin at the moment in my life when I am gutted with grief over the end of my marriage. In a miserable fog, I gratefully drag myself to the rehearsal studio that first day in September 2011. It is a respite from rumination about my failure as a wife. This is the place where I harness my overactive imagination by working through a process in the brilliant company of artists I admire and adore.

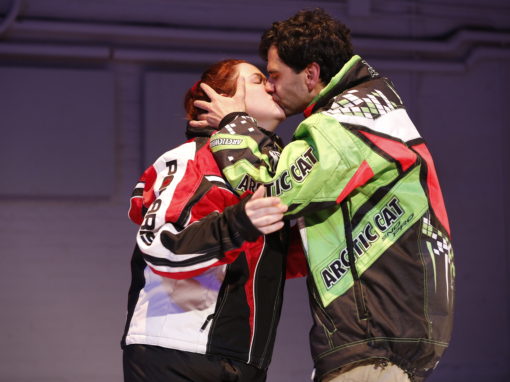

Queen of the Mist is the creation of composer, lyricist, and librettist Michael John LaChiusa. The inaugural project for Transport Group’s ten-year cycle of curated and commissioned works, The 20th Century Project, Queen of the Mist tells the story of Anna Edson Taylor, a 63-year-old widow, who becomes the first person to go over Niagara Fall in a barrel (of her own design) and live. The story examines this heroine’s bonkers obsession to perform a feat of incomparable daring. Further, Taylor attempts to capitalize on her successful fall over the Fall by giving lectures in town halls and Chautauqua tents describing her act while reaping the financial rewards and the acclaim she believes her due. It does not turn out so prettily for her, however: she is swindled of her earnings by her unscrupulous manager, and she’s reviled and disliked for her lecture style. Eventually, she dies in 1921—blind, penniless, unsung, and buried in an unmarked pauper’s grave.

I get to explore multiple roles in this piece, including Anna Edson Taylor’s sedate, put-upon sister Jane; a trash-mouthed vaudevillian (screeching the most significant line I’ve ever had the pleasure to deliver); a goggle-eyed citizen of Buffalo, New York visiting The Pan-American Exposition of 1901; a member of The Temperance Movement; a water spirit; and a gentleman who helps Annie out of her barrel after her stunt. He’s in the foreground right behind her in this well-known photograph, captured as onlookers guide the dazed adventurer to safety.

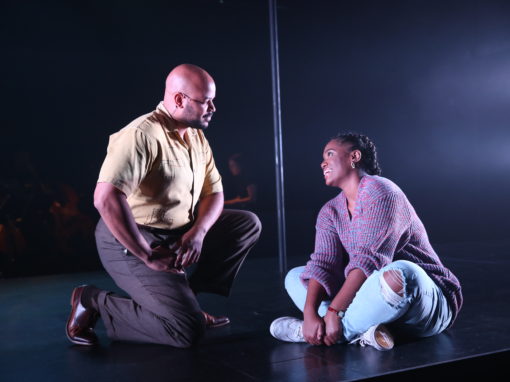

It’s a relief to lose myself in these roles, this music, this company of players who are delightful and smart. It’s a rare treat to go to rehearsal every day and die with laughter, to gasp in awe at the ingenuity of Stanley Bahorek, Julia Murney, Andrew Samonsky, D.C. Anderson, Tally Sessions, and Mary Testa (to me a queen, a sister, and a few years later, in another piece by LaChiusa, my mother). I worship at the altar of Michael John LaChiusa—singular artist that he is. His creations are psychotherapy for me, intricate puzzles that open my heart to shocking, delicious revelations about art and life. Finally, anyone who has worked with director (and Transport Group Artistic Director) Jack Cummings III understands that it is impossible to refuse a chance to be in a project he directs. He’s asked me not to go on too long about him here, so I won’t—but you know what I mean, you lucky ones!

I must admit this, though, and I’ve never said this to anyone: joining a rehearsal process is especially difficult at this time because I am still teaching acting full-time at NYU Tisch Playwrights Horizons Program, and I am a mother of four children ages 7-16. I intend to neglect my family in order to satisfy my yen to play in the company of creative geniuses. In spite of this (also because of it?), I am alive to the lucky strike that each small moment unveils in rehearsal. I aim to discover how to carry on despite the perils of my everyday experience. The process provides treasure richer than any paycheck, more too than positive critical response and accolades of my peers. I don’t care if I never work on a play or musical again after this project. For the last half of my working life, it’s my habit to (stoically? pessimistically?) insist that each piece I work on will be my swan song to the stage. So, the next act for me, hero of my own life story, is to putter in blissful retirement (perhaps a hermit, unseen, unattended by another—clearly husbandless!) in a pastoral setting, tending my garden, knitting quietly by a cozy fire, satisfied, while subconsciously pondering the possibility of getting back on the boards again.

LaChiusa’s writing is a delicious whole-body experience that challenges the actor’s intellect, emotional agility, as well as physical prowess. He never states the obvious. He is generous and patient with his collaborators as he waits for them to catch on to his ingenious inventions. This lyric from later in the piece hints at his impossible thesis:

The quintessential hero has to delight—she must delight.

We understand that the author will attempt to prove that undelightful individuals are worthy of admiration. One most startling truth about LaChiusa’s writing for Queen of the Mist is that his characters are NOT meant to charm. Instead, he is incredibly attentive to examining the motivations of the underdog. In a typical musical theatre work, roles provide an exciting opportunity for actors to show off, to seduce. Michael John’s people are not written to capitalize on an actor’s impulse to woo an audience. Queen of the Mist does not require the audience’s approval of the performers’ singing, dancing, and acting skills in order to be appreciated. To be sure, the work is terrifically challenging. Queen Mary Testa is onstage for nearly the entire piece, singing and acting as if her life depends on it. Despite this, viewers, you should not focus on the craft that goes into making a work of this caliber. Instead, you awaken to that urge—one you recognize within yourself—to survive the plummet over Niagara Fall (in a barrel that you have designed) that is your life. You want to justify this plunge. You want to know the reward of your richly lived experience. You will find on your barrel ride that there is no ready redemption. You take yourself over the Fall for no reason other than your soul compels you.

This profound truth dawns on me late in the process. Perhaps I’ve only realized it by writing these sentences. Before I understand what Queen of the Mist is really about, I consider the actor’s crucial questions about the character: Who am I? What do I want? How do I get it? What do I look like while I am getting it? These questions lead to the discovery that in order to properly play the anonymous man who helps guide Annie to shore, I MUST have a mustache. Why? Because the helpful stranger is mustached, he was a real person who touched Annie Taylor, who jumped to her service when she survived the Fall. Unfortunately, the budget for the Queen of the Mist does not allow for this extravagance. Undeterred, I don a metaphorical mustache for the moment needed toward the end of “The Fall”—Act II Finale. Do I mean the mustache is metaphorical, or is it imaginary? The mustache is invisible to the audience. But having made such a fuss about needing it to my castmates and Jack, I am fairly sure that they can see it. That detail for me is the transformative magic I need to become the metaphor: a spirit who guides the dying into the world beyond the world. Anonymous Mustache Man is a Psychopomp (of course, I looked this up—not my everyday vocabulary! Search terms: What is the entity that guides the dead to another realm?). I think he is, perhaps, Hermes or Charon if I am going to honor the Greek origin of term. These beings are noted in myths across cultures and history.

Psychopomp—a wonderful word, an even more wonderful force. One who carries a person who is lost. The spirit guide does not judge, cannot condemn the wanderer. Psychopomp is a midwife attending the birth of the new soul formed out of the pieces of a broken, flawed mortal. In the stunning final moment of Queen of the Mist, Annie Edson Taylor receives the empathy she never knew she deserved as ghostly, loving beings escort her to her heavenly throne. Annie sings in the Act Two Finale:

Beautiful world.

Terrible world.

Goodbye.

Into my barrel/coffin/cradle.

Goodbye.

Beautiful world.

Terrible world,

Farewell.

Into the water/gravesite/heaven/

Or hell.

I tell myself I do it for money.

Convince myself I do it for fame.

I justify myself with reason only the brave can name.

But I do it for more.

And what is the more?

I know there is more

Than

Sky.

Slate gray-blue.

Why?

People will ask.

There is no beautiful, terrible ‘why’;

No answer at all.

No answer to give.

Except to live.

And fall…

Why am I an actor? I have no sensible answer for this question I’ve asked myself the whole of my working life. And anyway, I am barely even an actor since I work so rarely. When I do work, I continue to perform my day job to support my family—my family, whom I love and neglect when I’m in production. I have felt like Annie Taylor—uncompromising, resented, jealous, unloved, unlovable. I have lied to the people I adore about my reasons for needing to work with incredible artists for a few months. It was not to earn a dollar or to advance my “career.” I’ve stolen hours and months away from my children and my ex-spouse in order to feel the thrill that comes from being a part of the ineffable process. I would do it again to have the chance to wear that mustache, to act as a psychopomp, and especially to feel the grace of my fellow players as we guide and lift one another for no reason other than to live and fall.

About the author:

Explore Our Past Shows