Lighting the Way // by Jen Schriever

Lighting designer Jen Schriever steps up as scene partner in BROADBEND, ARKANSAS.

Illuminate: v. 1. light up. 2. Decorate 3. Help clarify or explain.

A lighting designer’s job often varies greatly per project. Sometimes the task is somewhat straightforward: “support the realism of this very specific and tangible room.” Other times supporting the music & lifting the energy is our most important task, achieved by composing dynamic images and transportive imagery. In my least favorite scenario, the job can be quite practical: “light the scene stage right so a scene change can happen stage left.”

However, often the task is less obvious and much more abstract. In many of my favorite projects the lights have to support a very real story in a non-literal space. The lights hopefully help to guide the story back and forth through time, location, inner thought & outward emotion. The lighting can also take the audience on a psychological journey, by adjusting how we see what is right in front of us.

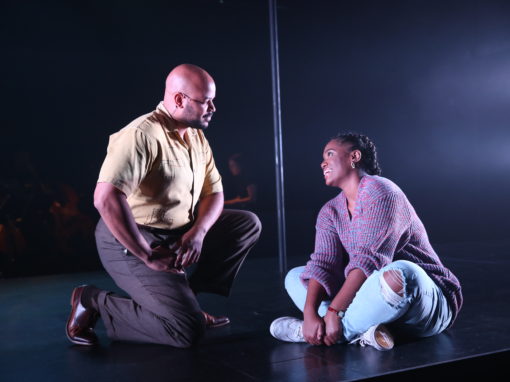

In the spare set conceived by my dear friend Dane Laffrey for Transport Group’s production of Broadbend, Arkansas, it became clear as a musical performed by a solo performer (Justin Cunningham in Act 1, and Danyel Fulton in Act 2) that the lighting would be taking on a role of abstract supporter & sometimes scene partner.

In our work sessions in the theatre, while we were unfurling and creating the piece that explores generational trauma & violence with a Black American family, we discovered the power of the void of the room surrounding the actor and the power in the very real energy that surrounds, envelops, and isolates Benny in Act 1 and his daughter Ruby in Act 2.

As we worked, we found that the light would literally trap Benny early in Act 1 at the nursing home and then wrap him with hope as he travels to join the Freedom Riders. In Act 2, the light needed to isolate and surround Ruby like the inescapable violence that surrounds her and then the light would support and rise with her inner power—as she electrifies with strength, she becomes the brightest light, a supernova of power and love, outshining the void.

It was also important that the light not offer any relief to the audience, as they confront this story, and this was one of my favorite things of the power of the storytelling in Broadbend, Arkansas: this story is being delivered by a single person on stage. The audience is not offered any relief or distraction. You are forced to stare, listen, engage with, and confront what you are hearing.

And isn’t that what we should be doing right now? In and out of the theater? We’re turning the lights on and addressing what we’ve been complicit in ignoring. We are confronting the very real stories of violence and oppression of our friends and neighbors. We must be the change in recognizing the generational trauma surrounding so many Americans and help to find relief. Now is not the time to be turning our heads away. Let’s keep turning the lights on.

About the author:

Explore Our Past Shows