The Goodness in The Time of Death // by Eunice Wong

In 1971, Fr. Daniel Berrigan wrote about duality in dark times. Actor Eunice Wong holds his words close.

My daughter Marina was baptized by Father Daniel Berrigan in 2011, when he was almost 90 years old. Father Dan, when I met him the day of the baptism, was a thin old man with white hair and a shuffling step, in a black paisley silk shirt. He didn’t wear a collar. He didn’t look like a priest. I knew, vaguely, that he was an important activist. I was impressed when he held Marina carefully on his lap and spoke about marching with Dr. King in Selma. During the ceremony he asked everyone in his whispery voice to bestow a wish upon our baby daughter. He went first: “I wish for you, a sense of humor.”

Seven years later, in the summer of 2018, Jack Cummings III contacted me and said he had an upcoming show I might be right for; could we have lunch? (Crêpes, actually.)

The project was The Trial of the Catonsville Nine by Daniel Berrigan.

Well.

Daniel Berrigan is not a household name in the twenty-first century. In 2018, this was an obscure text. Jack yelped when I told him that not only had I heard of Berrigan, but he had baptized my daughter. The play was taken from the court transcripts of the 1968 trial of nine Catholic activists, who raided a Vietnam draft board in Catonsville, Maryland, stole 378 draft files, and burned them in the parking lot with homemade napalm. They stayed, praying, until the police arrived. Daniel Berrigan was one of the nine. I had to do the show.

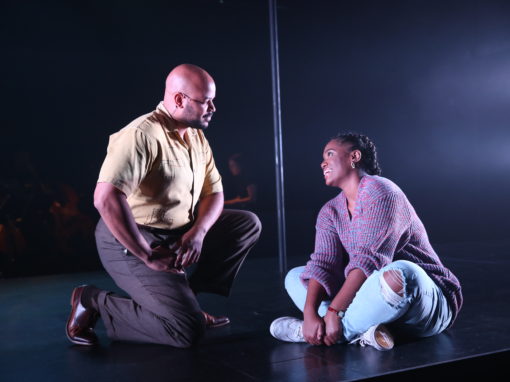

I played Dan Berrigan. I read his books, watched interviews and documentaries, listened to his poetry readings. I thought of the frail old man in the paisley shirt. I wondered at first if the production might be a dry, historical, Important Piece of Theater. I was wrong. Once the ideas—the fight, the struggle—came through our bodies, I was unprepared for the currents of live, almost unmanageable emotion running through me.

After the show closed, I took home a few photos from the hundreds scattered on the set, designed by the incredible Peiyi Wong. One is a black and white photo of two Vietnamese children in rags, seen from the back. The little boy is about four; he has no pants. He reaches out to the girl, who is maybe eight or nine. In the background are soldiers with machine guns.

I remember first seeing this photo on the set. It took my breath away. I see my own kids in this photo, my son, my daughter. Abandoned, trying to survive, surrounded by peril. Now, my children are safe, cared-for, well-fed, well-clothed, warm on cold nights. They are privileged first-world citizens and go to excellent schools. They have everything they need. They are loved beyond measure. But it is not inconceivable—and this thought has shaken my very core for years now—that they may be the last or second-last generation of humans on this planet.

This is not hyperbole. The oceans are rising, warming, dying. There could be fishless oceans by 2048 due to overfishing and pollution. Arctic ice sheets are breaking off in chunks the size of cities. Global atmospheric CO2 levels are the highest they’ve ever been in human history and they’re climbing uncontrollably, far beyond the levels we need to remain at for a livable planet. Birds and insects are falling out of the skies. Dozens of species are going extinct every day. The rainforests are being leveled at the rate of one football field every six seconds, mostly to graze cattle and grow monocrops to feed livestock, all for human consumption. The horror of biofeedback loops: the faster something changes, the faster it will change.

I cannot truly express the terror I feel at this. I seem to have an inexhaustible wellspring of grief.

Every night during The Trial of the Catonsville Nine, standing next to the audience in their pews, I said, as Berrigan, “The times are inexpressibly evil. And yet—and yet… the times are inexhaustibly good. In this time of death…”

This time of death. I looked into every face and meant now, every night. This moment we’re living in. Right here. This is the 59th minute of the eleventh hour. As we sit on the stage of the historic Abrons Playhouse, in New York City in the winter of 2019, after the good dinner you had before the show and before you go out for drinks and then head home, this time we are living in now, this time of death: I mean now.

And yet—and yet… the times are inexhaustibly good. It’s true these times are roiling with hatred and fear, ugliness and desperation. Poverty. Brutality. Gross injustice. Racism. Misogyny. Bigotry. Hypocrisy. Children torn from their parents and put in cages. The absence of simple decency. Lies, lies, lies. And now a global pandemic that arose from the rapacious desire—not the need—to kill and consume other animals. It’s true that human beings have destroyed this planet, turning the natural world and other humans into commodities. The world is on fire. The world is drowning. The world is on fire.

And yet. And yet.

There is still goodness. There is still love. There is still joy and hope. Hope that the children and grandchildren we cherish may get a chance to live out the span of their natural lives and be happy. We help each other because we wish to ease another’s pain. We learn about this astonishing earth we live on; we share the knowledge with wonder. We make glorious music, place pigments on surfaces to create art, we move our bodies to express what it is to be human, to be alive. We write. We imagine what it is to be other people, to feel what they feel. We tell dumb jokes to make each other laugh. We tell each other stories. We hunger for these stories because that is how we grow as humans, and we want to grow. We yearn for it. That is the sign of a living thing.

Goodness remains—precious, unspeakable, wordless goodness—it remains amidst the hatred and the fear, the ugliness and injustice. Whatever happens to us, there will always be goodness. Whether there are humans or not. Goodness in how a mother bear enfolds her cubs. In his poem “Credo,” Robinson Jeffers offers this about beauty, but I read it with goodness in mind:

“The beauty of things was born before eyes and sufficient to itself; the heartbreaking beauty

Will remain when there is no heart to break for it.”

And still—or therefore—I feel the deep, fathomless grief. For the music. For the children. For the stories.

But this is not cause to shrivel. This love–for there is no grief without love—is cause for the opposite: for the commitment to live your life according to your values. The Nine acted knowing that they would be arrested, indicted, and imprisoned. They still did it. They did it because it was right. And maybe that’s all anyone can do. In Berrigan’s words, “I knew then I must speak and act against death…”

I look back on that day in 2011 when Dan—I now consider him a dear friend—baptized Marina. I had no idea. No idea who, or what, I was sitting in that room with. I feel as though I’d turned my head at the exact wrong moment and a comet blazed by behind me—and I missed it.

There is something incomparable for an actor about portraying a real human being and attempting to honor and live their life deeply from the inside. It is an extraordinary bond. What I wouldn’t give now to sit with him quietly and ask him about his life. I had no idea.

After the final performance, my husband Chris gave me the best closing present I’ve ever received. A framed newspaper photo from 1968 of Daniel Berrigan, exiting the Baltimore courthouse. He’s calling out, his hand lifted high in a peace sign. Below the photo is an autograph of Berrigan’s, along with a short message in his handwriting—Chris had cut it out of a signed book. The message reads:

thank you for your visit and friendship!

–Dan Berrigan

It’s now next to the photo of Dan, age 90, frail in his black paisley shirt, holding our baby daughter in his arms and speaking of marching in Selma.

Thank you, Dan, for your visit.

About the author:

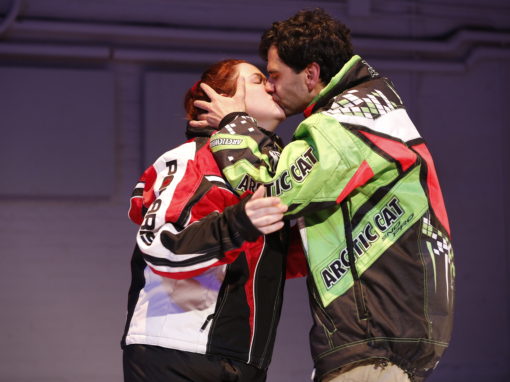

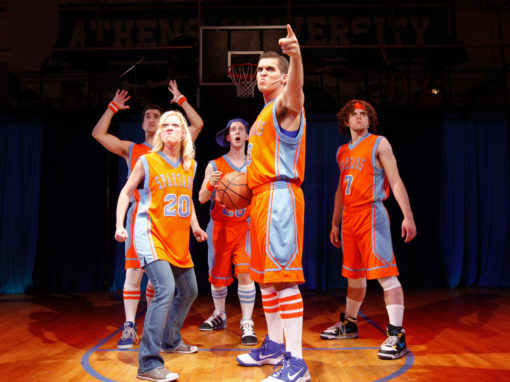

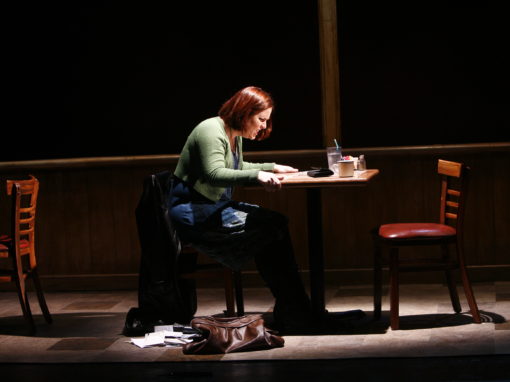

Explore Our Past Shows